The following profile has been adapted and is republished with permission from The National Registry of Exonerations.

Aaron Patterson, 25, and Eric Caine, 24, were tried together in 1989 and convicted by separate juries of stabbing an elderly couple to death on the South Side of Chicago. The mutilated bodies of the victims—Vincent Sanchez, 73, and his wife, Rafaela, 62—were found in their home on April 19, 1986. Caine and Patterson were arrested 11 days later after a 15-year-old girl claimed that Patterson had admitted the murders and a neighbor claimed to have seen Caine across the street from the Sanchez home around the time of the crime.

A tortured confession

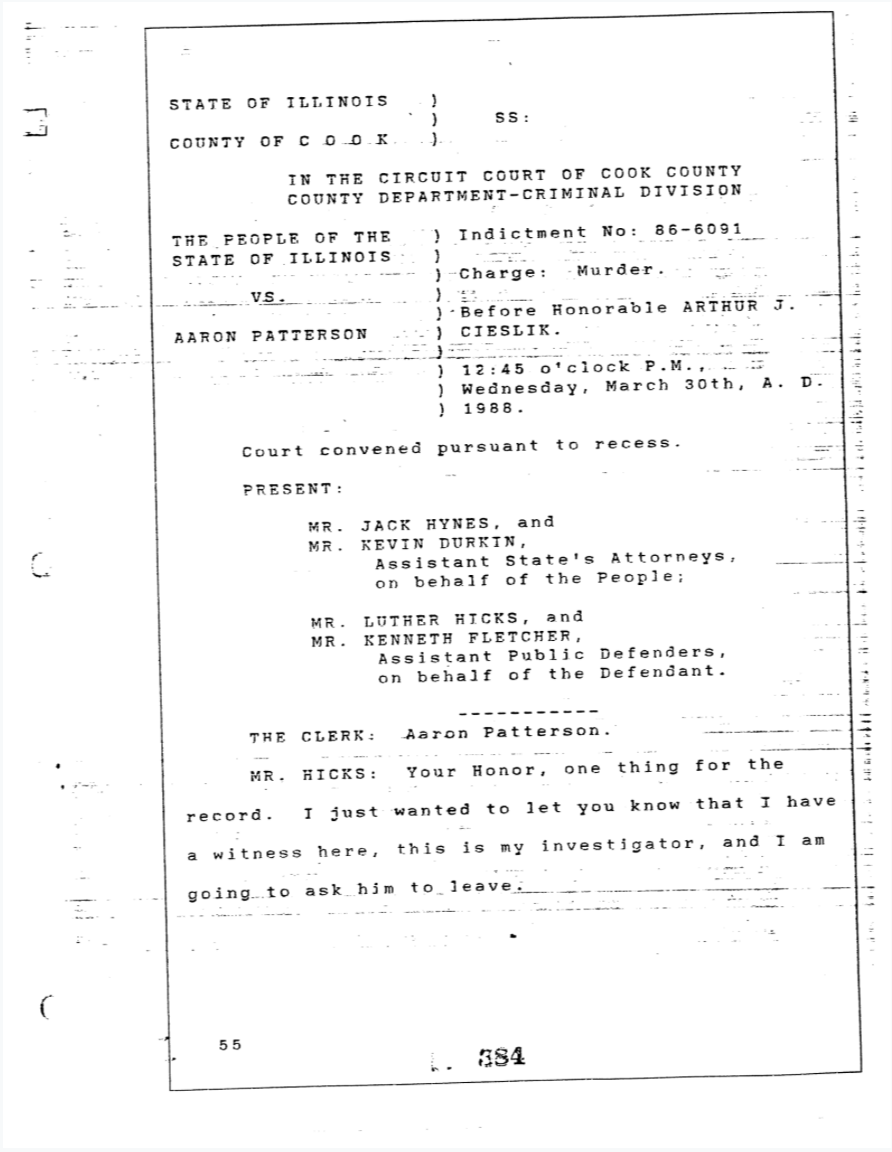

Detectives who were proven to have routinely tortured African American criminal suspects promptly obtained confessions from both men. Before their joint trial, Caine and Patterson moved to dismiss the confessions on the ground that they had been tortured. Caine testified that a detective told him that Patterson, the son of a Chicago police officer, already had confessed that he and Caine had gone to the Sanchez home intent on finding weapons. When the couple would not give up the weapons, Patterson began stabbing them and Caine ran. When he refused to go along with Patterson’s story, Caine testified, he was beaten and then taken to see Patterson, who had been so badly beaten that he could barely speak. Caine signed a confession.

Patterson was given a written statement to read and left alone, chained to a hoop on the wall of an interrogation room. With a paperclip, he scratched a message onto a metal bench: “Police threaten me with violence. Slapped and suffocated me with plastic. No lawyer or dad. Sign false statement to murders.”

Judge John E. Morrissey denied the motion to suppress the confessions, and the defendants’ separate juries found both guilty. Patterson was sentenced to death and Caine to life in prison. Caine and Patterson lost various appeals until 2000, when the Illinois Supreme Court belatedly recognized in Patterson’s case that “substantial new evidence supports defendant’s claim that his confession was the result of police brutality,” and ordered the evidentiary hearing on Patterson’s torture allegations. At that point, the young woman who, at age 15, had implicated Patterson in the murders, admitted that she had lied to protect her cousin, who had been an alternative suspect in the case.

A plea for a pardon

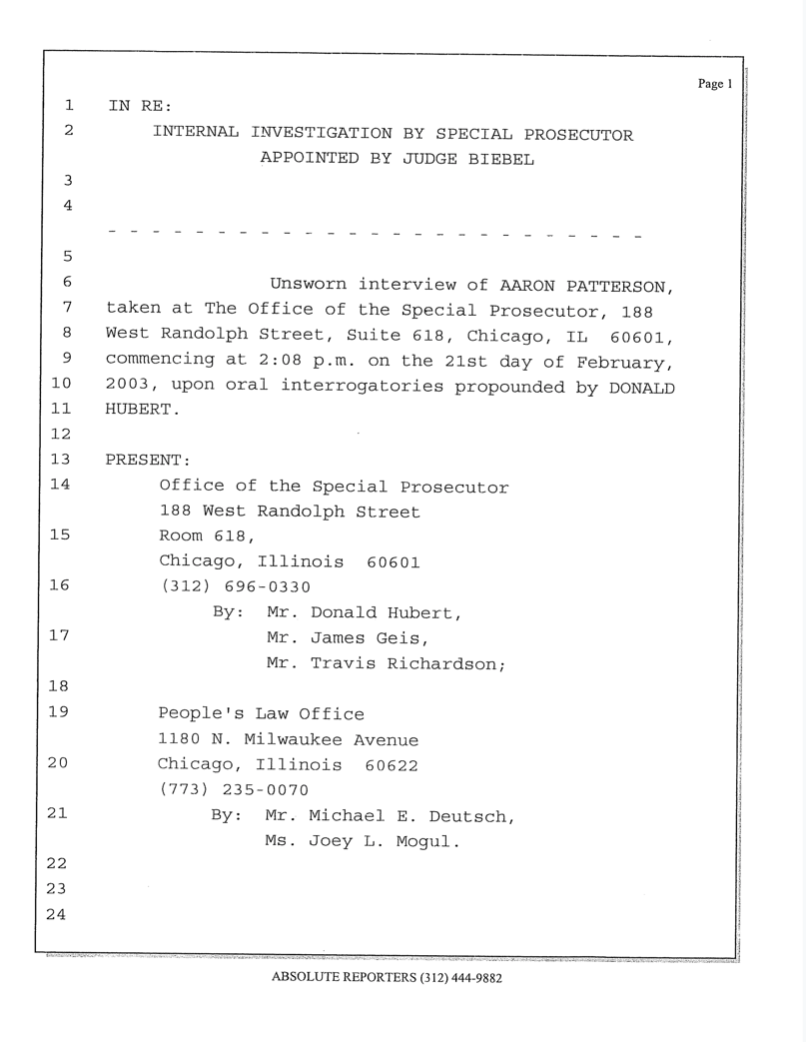

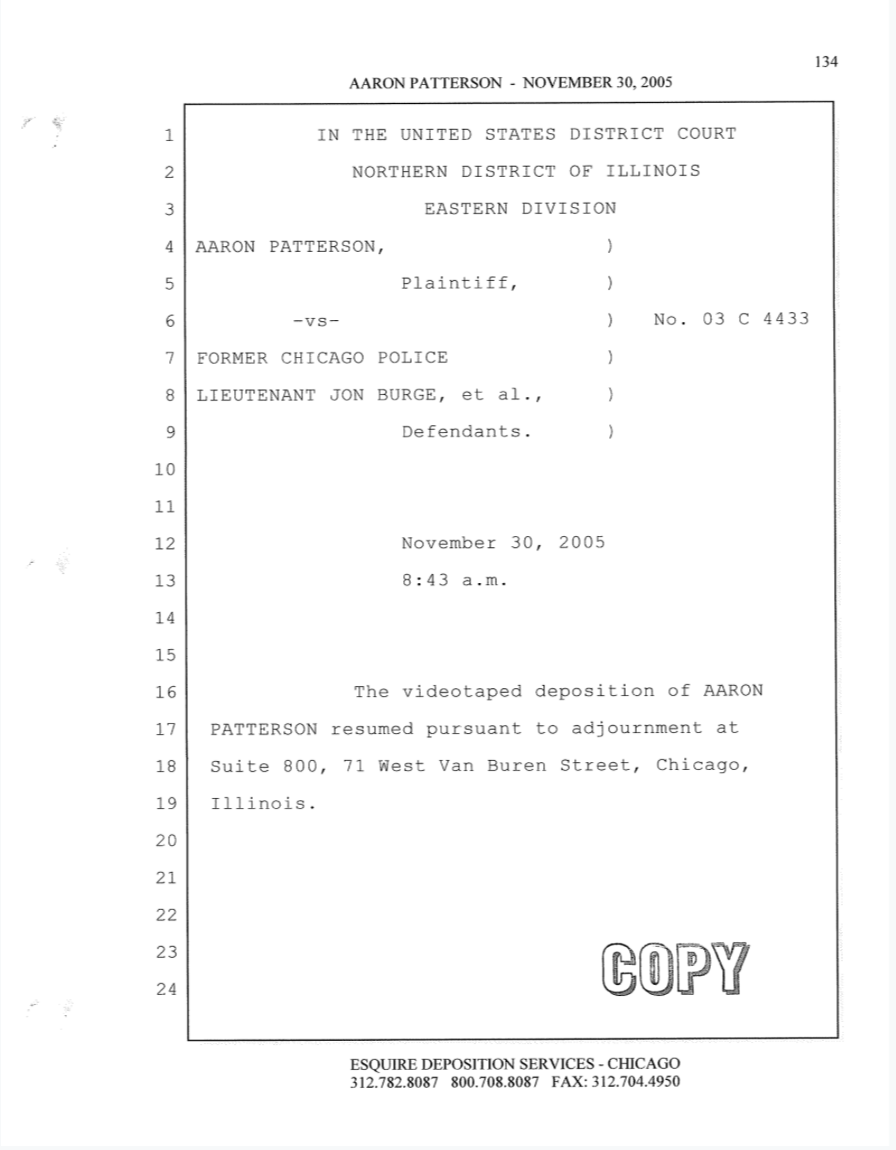

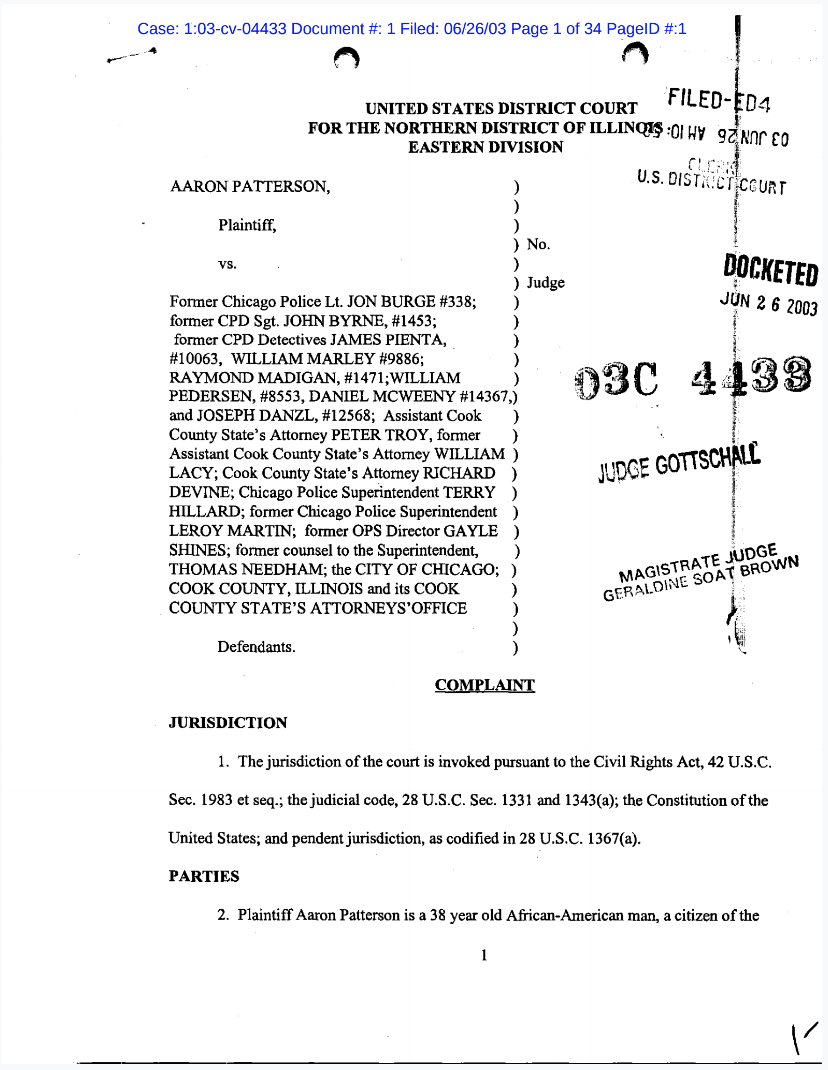

Patterson’s attorney, G. Flint Taylor, Jr., filed a petition seeking a gubernatorial pardon based on innocence, which Governor George H. Ryan granted on January 10, 2003, freeing Patterson. At the same time, Ryan also pardoned Madison Hobley, Leroy Orange, and Stanley Howard—who also were tortured. In 2007, a federal civil rights suit brought against the police by Patterson was settled for $5 million. Patterson also received $161,578 under the state compensation statute.

Also in 2007, Patterson was sentenced to 30 years in prison after being convicted in federal court of gun and drug charges.

Caine, however, was not pardoned because he “only” received a life sentence.

In 2009, the Exoneration Project at the University of Chicago’s School of Law filed an Amended Petition for Post-Conviction Relief, asserting that Caine’s confession was coerced and introducing new evidence of misconduct by the officers who interrogated him. The petition also introduced new evidence identifying the true perpetrators.

On March 16, 2011, 25 years after his conviction, the state of Illinois dismissed all charges against Caine and Cook County Circuit Court Judge William Hooks ordered his release. Caine was released the following day—the same day that former Chicago Police Lieutenant Jon Burge, who had led the police unit that tortured Patterson, Caine, and many others, entered prison after being found guilty of perjury and obstruction of justice related to the torture of criminal suspects.

— Written by the Center on Wrongful Convictions