The following is adapted from Exoneree Diaries: The Fight for Innocence, Independence and Identity by Alison Flowers of the Invisible Institute:

“Imagine how badly they must have beaten me for a Cook County judge not to be able to look the other way.”

Born to a single mother in Michigan City, Indiana in 1965, James grew up mostly on the South Side of Chicago. The oldest of five siblings, James never knew his father. He doesn’t even know his name. But he remembers being close to his mother.

While he was growing up, James’s family was on public assistance. Other than that, his mother received support from whomever she was dating at the time. James’s last name, Kluppelberg, came from one of her husbands, who adopted him. He has no idea where this man is today.

Once a month, when James was little, his mother would shop in the middle of the night at a 24-hour Jewel grocery store. She would take James with her as she stocked up for the whole month with the family’s food stamps. “That used to be our time,” he says.

In the mid-eighties, James was in a relationship with a woman named Dawn; that relationship would determine later events that led to his wrongful conviction.

In 1984, Dawn had briefly left her boyfriend and the father of her three other sons, Duane Glassco, for James. During their relationship, Dawn and James lived together, and James helped take care of her kids. Duane, a drug addict with nowhere to stay, shacked up in the home, too.

In the early Saturday morning hours of March 24, 1984, a blaze overtook a three-story wood-framed apartment building on the South Side of Chicago. Elva Lupercio woke up her husband, Santos, to tell him the house was on fire. He scrambled to gather their five children around him: 10-year-old Santos Jr., 8-year-old Sonia, 6-year-old Crisabel, 4-year-old Elva Yadira, and 3-year-old Anabel.

The family on the third floor was able to get out.

Before he could save his family, the floor gave way and Santos crashed to the bottom, becoming severely burned. He was taken to the hospital. He never saw his wife and kids again. They were all pronounced dead at Mercy Hospital within hours of the fire.

Living several doors down from the fire, James, along with many other neighbors, had watched as the flames consumed the building.

That night, James had been playing cards with Dawn and Duane. It had been a frustrating night. James had come home to find the pair high on angel dust, a nickname for the hallucinogen PCP.

The kids had not eaten, and the house was a wreck. To cool off, James walked his collie-shepherd mix, Bootsie.

When he returned, he quarreled with Dawn and left again with the dog.

The community reeled from not one but two fires in the neighborhood. A Back of the Yards Journal article, just a few days after the incidents, reported: “Two Tragic Fires; Six Perish, Many Homeless.” In the same paper, a columnist wrote about an “arsonist on the loose,” asking, “Who is burning these houses?”

The Back of the Yards Council sponsored a fire victims’ fund and planned to sell smoke alarms for $8.15.

The city’s only fire investigation unit at the time was the Chicago Police Department’s Bomb and Arson Unit. Investigators could not determine how or where the fire started because the building had collapsed.The case was ruled an accident and closed.

Duane, then 23, was facing burglary charges, arrested on felony probation, and he saw the opportunity to get a break on his case. And he could finally retaliate against James. Duane’s jealousy over Dawn’s leaving him for James in 1984 had not subsided.

Duane made up a story, telling police he had witnessed James going back and forth to the apartment building the night it burned down in 1984. Duane added to the lie, saying he could see James about a block away through the attic window of the home. Another building obstructs the attic view, a fact that would not fully emerge for more than two decades. Their landlord also kept the attic window boarded up in the winter to retain heat, Dawn would later reveal.

In January 1988, 22-year-old James was repairing frozen pipes at an apartment building on South Hermitage Avenue when police came for him in the evening.

They put James in at 10-foot-by-12-foot interview room with a tinted one-way mirror window. The space had two doorways, one leading out and the other leading to a lieutenant’s office. “I got scared. I got real scared,” James says.

He called his lawyer, who wasn’t in. He then agreed to take a lie detector test, but just beforehand, police handed him a waiver that stated he would be asked questions about homicides from 1984.

James stopped. “I asked them what they were trying to do, and that is when the officer got violent and slammed me up against the wall and put a pair of cuffs on me and dragged me back upstairs,” James would later testify at a hearing leading up to his trial.

The interrogation turned into a beating, which led to James’s confessing to having set the fires, he says. “They laid me face down on the floor and they started punching me in my back and using the heel of their feet in the back kidney area,” James described.

At one point, the beating had stopped long enough for James to use the bathroom, and he realized he had urinated blood. “There was blood in my underwear,” James remembers.

Disoriented, he had lost his sense of time when an assistant state’s attorney showed up to jot down nine sentences, summarizing James’s “confession” to police at about half past midnight.

He was not alone with the assistant state’s attorney to divulge he had been beaten. The police kept him there, claiming that James had intentionally set the car fires he had reported, constituting a parole violation from his 1984 burglary convictions.

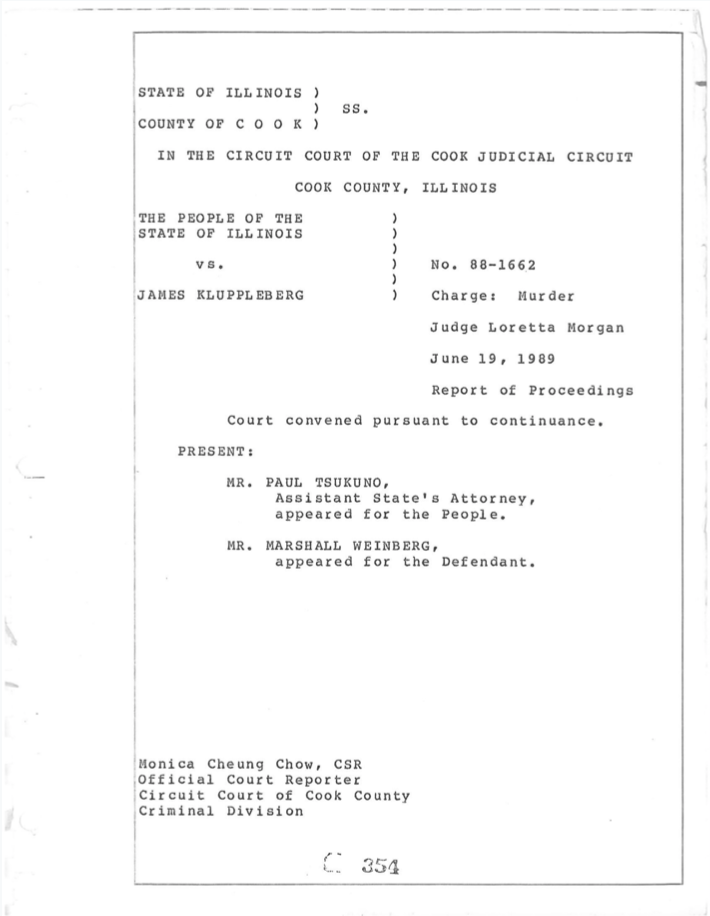

James called his lawyer Marshall Weinberg and told him that he’d been beaten. Weinberg instructed him not to make any more statements to police or prosecutors. James was taken to the county jail, being held for the car fires until a murder indictment could come down.

The booking officer at the jail noticed bruises on James’s lower back and kidney area. James told him he was urinating blood. An intake form showed two large markings on a diagram, right where the kidneys would be. When Weinberg visited James in lockup, James pulled up his shirt, revealing several large bruises on his lower back. Weinberg asked a judge to send him to the county jail hospital for treatment.The court ordered it, but James says he was never sent. It took another week before James received medical attention in jail. He was found doubled over in the bathroom. “They ran some tests, gave me some meds, and sent me back to the deck.”

About a week later, Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge, now infamous for his decades-long torture campaign, announced to the media his department’s triumph over the 1984 arson case. They had obtained a confession, he reported.

“Klupperberg [sic] told us he had been setting fires since he was nine years old,” Burge told reporters. The statement was a total fabrication, one that did not even match the forced confession that was beaten out of James.

Indicted for the Lupercio family murders, James’s hopes were high that the truth would prevail and he would be set free to return to his family. He sat in county jail for a year and a half waiting for his trial, waiting for justice.

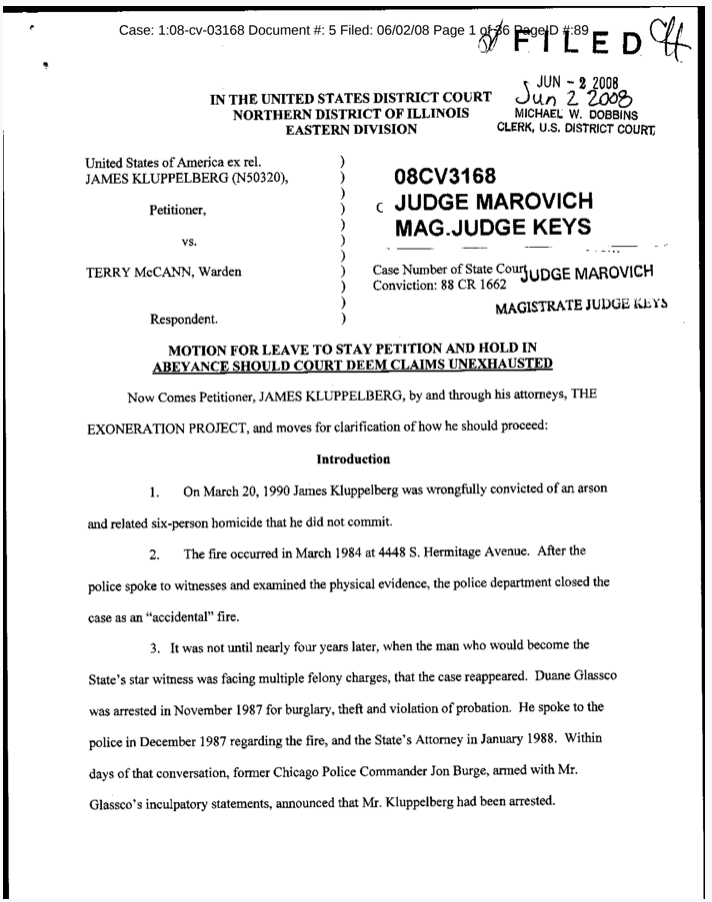

Weinberg continued to represent him, and, before the murder trial, he succeeded in having James’s forced confession tossed out. “We cannot have statements that are the result of mistreatment by the police,” Judge Robert Collins said after a lengthy hearing in November 1988. “There is no disagreement in that area.”

But the case itself would still go forward on the testimony of a single eyewitness, Duane.

At a bench trial in July 1989, prosecutors presented a purported arson expert, Commander Francis Burns, who had worked in the Chicago Fire Department’s Office of Fire Investigations, which was not operating at the time of the fire. Burns had not conducted an official investigation of the fire. In 1984, the Chicago Police Department’s Bomb and Arson Unit handled such investigations and had ruled the fire an accident, closing the case. But for a training exercise, Burns had never investigated the site of the fire, taking no notes and making no reports. At trial, relying only on memory, Burns told the court about V-shaped burn patterns he had observed, which made him think the fire was an arson.

Having made a deal with the prosecution on his own case—three years in prison considered time served—Duane then testified. After a burglary conviction, he was due to be sentenced for a probation violation, and he wanted leniency. In the U.S. criminal justice system, backroom deals like these are not uncommon, as many cases are brokered without a trial.

In court, at James’s trial, Duane said he was coherent the night of the fire, despite having taken cocaine. His ex-girlfriend Dawn also said they had been taking animal tranquilizers called “tic”—angel dust. “And I asked him what he did, and the only thing he did was smile at me,” Duane told the court about seeing James the night of the fire. “You can see the whole yard from the window.”

James was angry. “I just sat there in amazement and awe that he had such a vivid imagination.”

The trial lasted about eight hours over two days. Then: Guilty. James was stunned.

“It doesn’t take much to convict a person,” he says. “It does not take anything more than what somebody says.”

Even more shocking to James: the state wanted the death penalty.

“I was never told,” James says. “It freaked me out.”

As he awaited sentencing in the fall of 1989, with nothing to lose, James escaped from jail on a bribe. Officers in tactical gear eventually showed up to his hotel room as he fled to Florida.

It would be another 23 years until he would walk without chains.

—Written by Alison Flowers