Around 9 p.m. on July 6, 1985, two men approached an ice cream truck. One of them had a gun. A third individual waited for the men in a car nearby. The ice cream truck was parked by Fernwood Park on the city’s South Side and was manned by Enos Conard, 49, and his son, Troy, 24.

One of the men asked the younger Conard for an ice cream bar. While he turned, the armed suspect pulled out a gun and pointed it at him. When Troy turned back around, he had a gun pointed at him and was warned not to speak or move. Troy, however, alerted his father, who reached for his own gun. The suspect then fatally shot Enos Conard a single time in the chest.

The two men took off running. According to court records, they were picked up a few blocks away by the third individual in a car and fled. Troy spent the next two months combing through police photos and mugshots to try to find the men who killed his father, according to the Chicago Tribune.

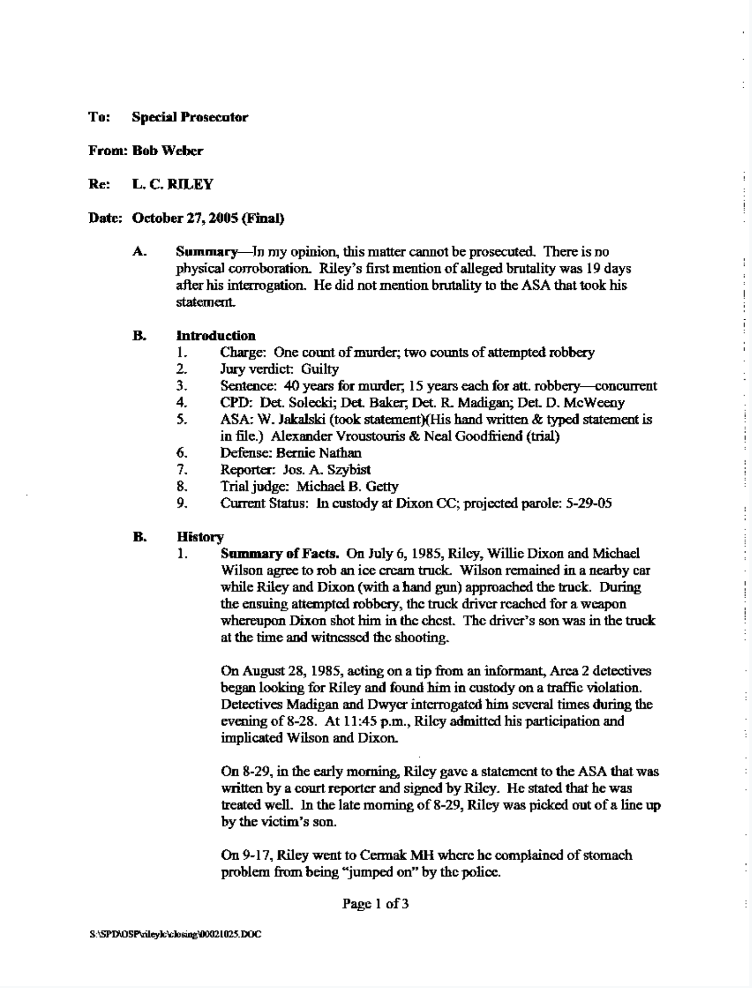

Police testimony later revealed that after a tip from a confidential informant the afternoon of August 28, detectives began looking for three individuals in connection to the ice cream truck murder. The informant, who claimed to have heard a conversation between the individuals involved in the crime, named the suspects as Willie Dixon, L.C. and Big Mike. Troy Conard identified Dixon, 35, as the man who shot his father from a photo array.

Detectives said they were out canvassing the neighborhood for the three potential suspects when they learned someone named L.C. had already been taken into custody.

Riley’s arrest

According to court records, it was around 4 p.m. on August 28, 1985, when police officers pulled 31-year-old L.C. Riley over for a broken taillight. The officers subsequently arrested Riley for driving on a suspended license. After his arrest, Riley said he was approached by Detectives Robert Dwyer and Raymond Madigan, Area 2 detectives who worked under police Cmdr Jon Burge. The detectives led Riley upstairs to a small room on the second floor of the police station.

In a 2016 interview, Riley said that at the time of his arrest he had been repeatedly targeted and harassed by cops in the neighborhood. He knew how Burge’s crew pinned cases on people and tortured them.

Police question Riley about the robbery

Once in the room, Riley said Dwyer and Madigan handcuffed him to a ring on the wall and began asking him questions about the ice cream truck murder. In later testimony, both detectives claimed they read Riley his rights before they began to question him and that Riley voluntarily waived those rights. Riley contends not only that this never happened, but that he also repeatedly asked for a lawyer, a request detectives ignored.

The detectives listed the names of several people, including Dixon and Big Mike, and asked Riley whether he knew them. Riley acknowledged that he knew both men and also told detectives that Big Mike’s real name was Michael Wilson.

The detectives pressed Riley for more information about the murder, at which point he again told them that he wanted to speak to a lawyer. When Riley refused to answer questions, he said the detectives turned off the lights and left him handcuffed in the room alone, taking turns coming back in every so often to try to get him to talk.

A tortured confession

After several hours alone in the dark room, Riley said Madigan came in to talk to him again. By now, however, Riley said the detective’s demeanor had changed. Madigan pulled him up off the bench by his shirt and demanded he tell them what happened. Riley later testified that Madigan also slapped the back of his head, punched him in the stomach and pushed him back up against the wall, painfully twisting his handcuffed arm. When Riley still refused to tell him anything without a lawyer present, he said Madigan slapped him again and left the room.

At one point, Riley also recalled, the detectives told him that he either needed to take responsibility for the ice cream truck robbery — or for an unrelated murder of a woman kidnapped from his neighborhood.

After 11 p.m., Riley said Dwyer came back into the room eating peanuts and asked if he was ready to talk. Riley refused. Dwyer threw a handful of peanuts in Riley’s face before grabbing him by the neck and punching him in the ribs. According to Riley, Dwyer then turned Riley around and searched him. When Riley again asked for a lawyer, Dwyer twisted up a newspaper and hit him between the legs, a blow which Riley said nearly caused him to black out.

At this point, Riley said he made a statement admitting his involvement in the ice cream truck robbery.

Convicted and sentenced to 40 years

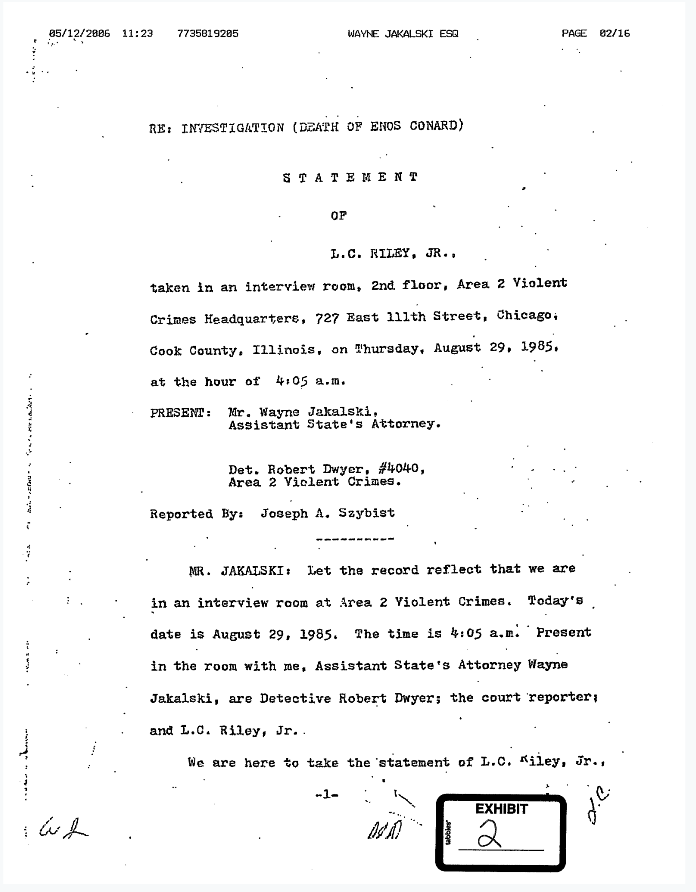

A prosecutor, with Dwyer alongside, took a court-reported statement from Riley at 4:05 a.m. on Thursday, August 29. The prosecutor was the first person to read him his rights, Riley later testified.

Riley said he experienced pain in his stomach and ribs from where he was hit by detectives and threw up while held in the district lockup. When the detectives moved Riley back upstairs to participate in a lineup, he said he asked for medical assistance; that request was ignored.

In the late morning on Thursday, Troy Conard, the victim’s son, picked Riley out of a lineup.

On September 17, Riley was examined at Cermak hospital, where he complained of stomach pain from the beating.

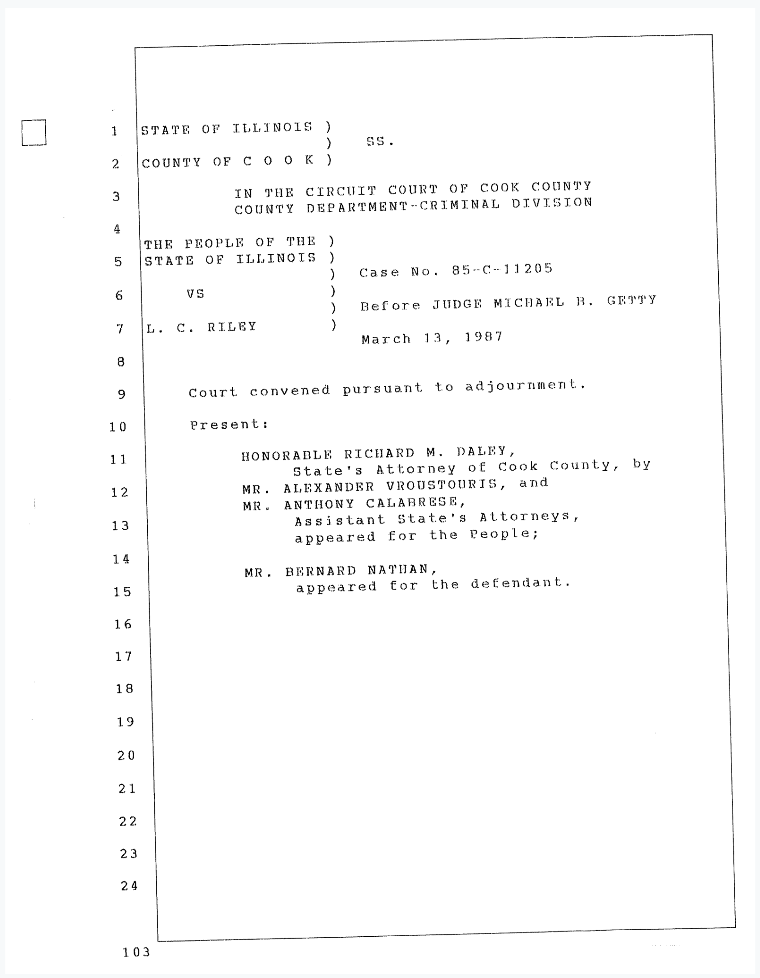

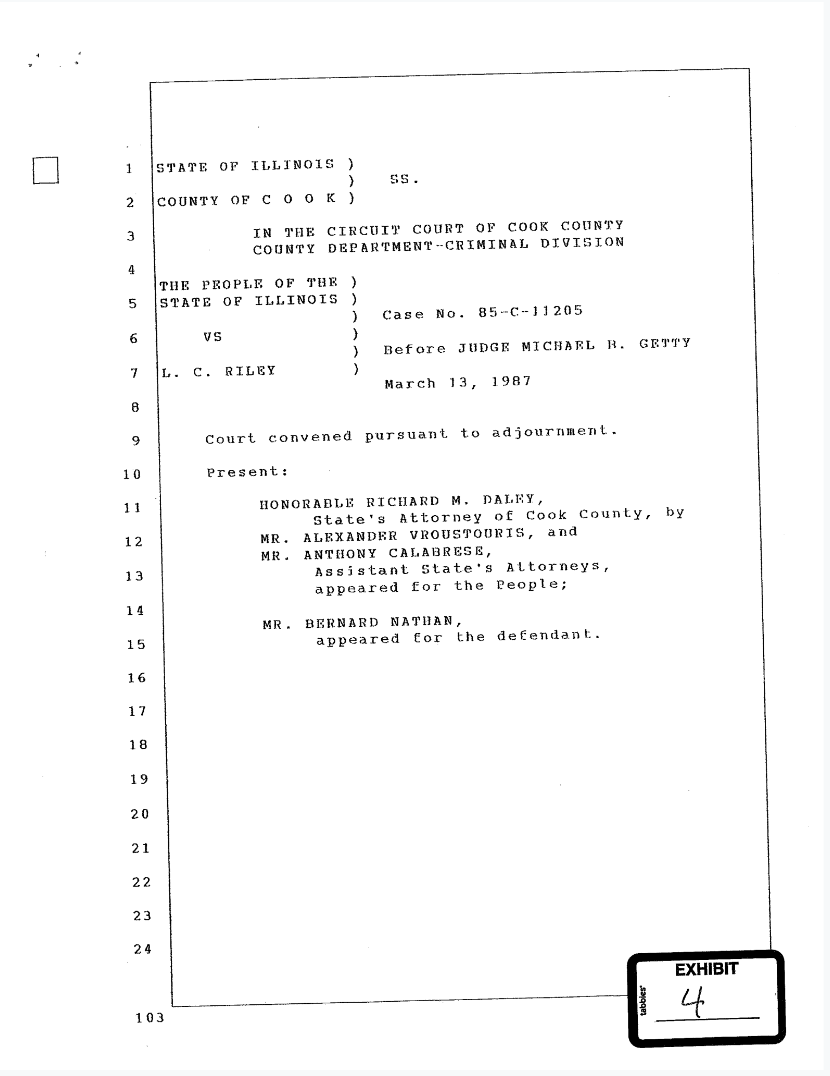

In March 1987, Riley testified in a motion to suppress hearing about the abuse he experienced. Detective Dwyer and Madigan, who had since been named a sergeant, also testified, denying ever physically hitting, threatening or coercing Riley. The judge denied Riley’s motion to suppress, and he was convicted. At trial, Riley was sentenced to 40 years for murder and armed robbery while Dixon, the shooter, received a life sentence. Michael Wilson, the getaway driver, testified for the state against Riley and Dixon and in exchange served only a few years in prison.

In 1992, the appellate court affirmed Riley’s conviction, and the following year the Supreme Court denied leave to appeal the decision.

Life after prison

While incarcerated, Riley said that he earned his GED and started training to become an optician.

When more information started coming out about the men whom Burge tortured, Riley’s case started to draw interest. A few years before he was released from prison, Riley said attorneys from the People’s Law Office visited him for a deposition to help build the case against Burge. Riley could not pursue a civil suit of his own due to the statute of limitations.

Riley was released on parole in May of 2005 after almost 20 years in prison. In October of that year, attorneys working with the Office of the Special Prosecutor investigated the allegations of torture against Burge and his men. The office concluded that Riley’s case could not be prosecuted due to a lack of physical evidence and because he did not report the abuse until weeks after his interrogation.

“You leave home one day and say, ‘I’ll be back in a minute,’ and you never showed back up,” Riley said in a 2016 interview with Amanda Rivkin. “They can take your life just like that without even killing you.”

Riley said he was happy when Burge was finally convicted of perjury in 2010.

“They ruined my life,” Riley said about how he had missed his children growing up. By the time Riley was released from prison, his children had kids of their own. “I was a granddaddy,” he said. “I missed all of their lives.”

— Written by Dana Brozost-Kelleher

Documents

Interview

July 25, 2016. Journalist Amanda Rivkin interviewed L.C. Riley.