Photo by Associated Press

In 1990, a jury sentenced Madison Hobley, a Chicago native who worked for a home healthcare services company, to death for the murder of seven people by arson—including Hobley’s wife and infant son. Hobley remained in prison for 16 years, 13 of which he spent on death row. He was pardoned in 2003 by Illinois Governor George Ryan on the basis of innocence.

The fire

Around 2 a.m. on January 6, 1987, 26-year-old Madison Hobley said he woke up to the sound of a smoke alarm. Hobley lived with his wife, Anita, and 1-year-old son, Philip, in a third-floor apartment on Chicago’s South Side. Hobley would later testify that he shook Anita awake before getting out of bed to investigate the alarm. When he opened the front door of their apartment, Hobley said he thought he saw smoke coming from under the door of an apartment down the hall.

“Anita, there’s a fire. Get Phil,” Hobley later testified he said before he went to warn a neighbor down the hall about the fire. Once he had walked down the hall, however, Hobley said he couldn’t get back to his apartment to save his family because of the intense heat and smoke that blocked his path.

Hobley questioned by police

Area 2 Detectives Robert Dwyer and James Lotito went to interview Hobley at his mother’s house several hours after the fire. Hobley told the officers he suspected a woman with whom he’d recently ended an affair.

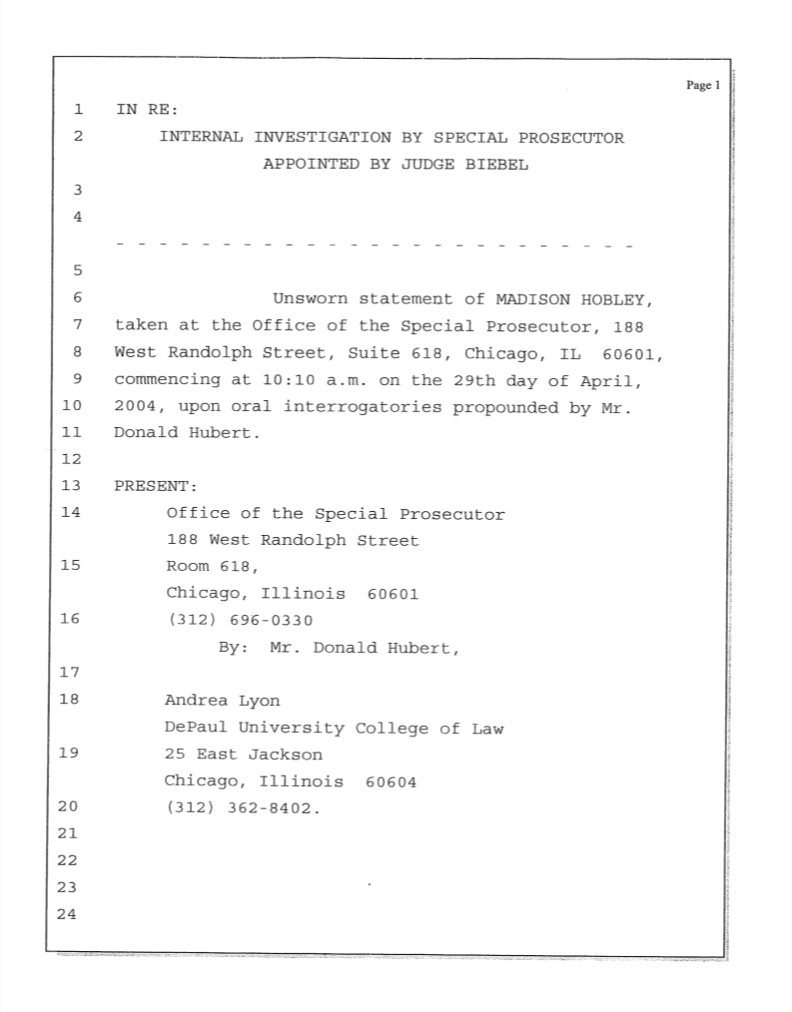

The tenor of the interview changed when Detectives Dwyer and Lotitio drove Hobley to Area 2 Police Headquarters for further questioning. Hobley testified Dwyer put him in an interview room where he immediately started to racially harass him and accuse him of starting the fire. Hobley described how Dwyer knocked off his hat, hit him in the chest, and handcuffed him to a ring on the wall. “I relive that every day,” Hobley later said in a statement to special prosecutors about the incident. “Before that,” he told a special prosecutor in 2004, “I never actually been in a fight or anybody ever put their hands on me.” Hobley also said during his 1989 trial that Dwyer pushed his thumbs into his throat and ribs. He later said that his requests to speak to an attorney were repeatedly rebuffed.

Hobley’s alleged confession

Two officers then transferred Hobley to police headquarters at 11th and State, where Sergeant Patrick Garrity, a lie detector operator, administered a polygraph test on Hobley, according to his later statement to a special prosecutor. Hobley again denied setting the fire when asked by Sergeant Garrity.

Despite Hobley’s adamant protests, Garrity soon told him that he had failed the polygraph and, therefore, must be lying. When Hobley asked for clarity regarding the polygraph, he said Sergeant Garrity kicked him in the shins.

Garrity later told Area 2 detectives that it was then that Hobley confessed—a version of events he denied.

Soon, Hobley was moved to a utility room at the 11th and State station where he was alone with Detectives Dwyer and Lotito, as well as a third officer later identified as Daniel McWeeny. There, Dwyer put handcuffs on him so tight that Hobley’s hands went numb, he testified. He then began to punch Hobley in the stomach repeatedly while demanding he confess.

While held in the utility room, Hobley said Dwyer also pushed his thumbs into his throat again and slapped him across the face. Another officer in the room kicked Hobley in the groin from behind. When Hobley still refused to confess, he said Detective Lotito put a typewriter cover over his head and suffocated him until he blacked out. “I thought I was dying,” Hobley later testified about being suffocated. “I thought they were killing me.”

When he awoke, Hobley remembers Dwyer again demanded he confess. Hobley says he refused, pleading with the officers that he was innocent. Still, Dwyer, Lotito, and McWeeny would later testify that Hobley had also confessed to them that he had started the fire.

“I felt like I was being treated less than human,” Hobley said in a 2004 statement to special prosecutors. “And the abuse hurt. The physical abuse and mental abuse hurt, and the accusations.”

Hobley takes on the Chicago Police Department

After an undetermined number of hours, Hobley testified that he was finally permitted to speak with a family attorney, Steven Stern, whom he told about the police abuse and who refused to allow any further questioning.

Detectives Dwyer and Lotito then drove Hobley back to Area 2, where he was formally booked into custody.

At his first court appearance on January 7, 1987, Hobley told investigators that he informed his public defender, Julie Harmon, about the abuse he suffered by police and the attorney had photos taken of his injuries. Before being admitted to Cook County Jail, Hobley was examined at Cermak Hospital. For reasons that aren’t clear from court records, the technician who did the exam never testified on his findings.

Convicted and sentenced to death

In 1989, Hobley went to trial for the murder of seven people by arson. According to court records, Hobley filed a motion to suppress his coerced confessions, which police say were obtained verbally the day of the fire. Dwyer later claimed he had thrown out written records of Hobley’s confession because he had spilled coffee on them. The judge, over Hobley’s attorneys’ objections, allowed the jury to consider the confessions in addition to Hobley’s testimony regarding police misconduct.

A key piece of evidence used against Hobley at trial was a gasoline can officers allegedly found on the second floor of the apartment building, which detectives said they discovered as a result of Hobley’s confession. According to a lawsuit filed years later, however, the officers involved in Hobley’s case withheld during trial that the gasoline can had been seized from an unrelated fire and planted in Hobley’s building hours after the apartment fire.

In 1990, a jury convicted Hobley of murder by arson of seven people, including his wife and son, and sentenced him to death. Despite efforts to appeal, the Illinois Supreme Court affirmed Hobley’s conviction and death sentence on May 27, 1994.

The Death Row 10

In August of 1987, while detained at Cook County Jail, Hobley made a statement to an investigator from the Office of Professional Standards (OPS) regarding mistreatment by Detectives Dwyer and Lotito. The officers involved denied any mistreatment of Hobley. OPS determined there was insufficient evidence to support Hobley’s claim of police abuse and closed the investigation into his case in 1991 following Hobley’s conviction.

While incarcerated, Hobley exchanged stories with other men on death row, who said they had also been tortured by Area 2 detectives into giving false confessions. For years, the group organized and helped raise awareness around the issue of police torture in Chicago. They became known as The Death Row 10 because they were all in prison as a result of confessions extracted by Burge or officers under his command.

Hobley would see little movement in his case for years.

However, in 1998, after a review of new evidence, including that prosecutors withheld information during Hobley’s trial and additional allegations of misconduct levied against the officers involved, the Supreme Court of Illinois ordered a review of Hobley’s conviction. A judge, though, denied Hobley’s post-conviction petition in July 2002.

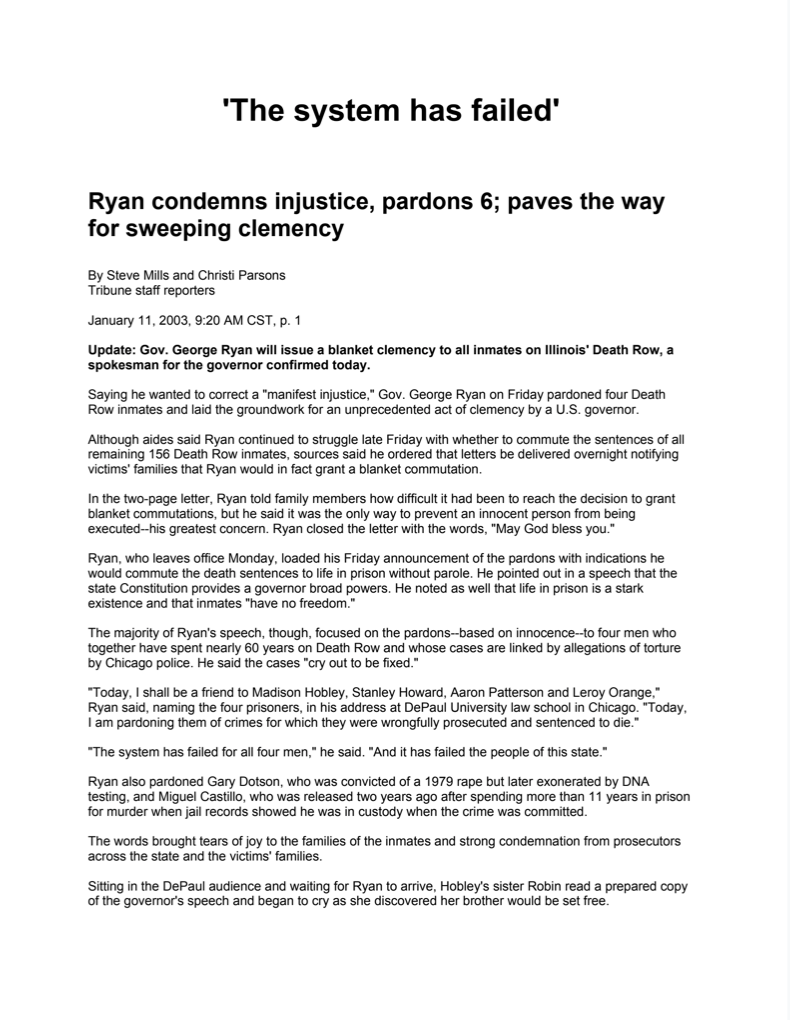

By the next year, however, Illinois Governor George Ryan would pardon Hobley and three other death row prisoners with allegations of torture against Chicago police. “The system has failed for all four men,” Governor Ryan said in a 2003 statement during which he announced the pardons of Hobley, Stanley Howard, Aaron Patterson and Leroy Orange, further characterizing their cases as ones that “cry out to be fixed.”

Life after Prison

Hobley was released from Pontiac Correctional Center on January 10, 2003, though his plight would not end there.

“I constantly have nightmares of the abuse that I just can’t let go,” Hobley said during a 2004 deposition for his civil lawsuit. “That was the first time ever in my life that someone told me that they actually hated me or anybody that looked like me.”

In 2008, Hobley and three other former death row prisoners received a nearly $20 million settlement from the city of Chicago. Hobley was awarded $7.5 million as part of the agreement.

While incarcerated, Hobley married his second wife, Kim, in 1994. Soon after his release from prison, Hobley found employment as an administrative clerk at Cascino Vaughan Law Offices.

—Written by Annie Nguyen and Dana Brozost-Kelleher