Journalism

The following is an account by journalist John Conroy, who exposed former Commander Jon Burge’s reign of terror inside the Chicago Police Department. Conroy first reported on the scandal in 1989 and continued to cover it until 2010, when Burge was convicted of obstruction of justice and perjury. Without Conroy’s persistence, the truth about the torture, which sent scores of wrongfully convicted men to prison, may never have become public knowledge.

In November, 1973, the Chicago Tribune published an eight-part series on police brutality. Reporters George Bliss, Pamela Zekman, William Mullen, and Emmet George wrote of rampant abuse by patrol officers who were never effectively disciplined. The series did not deal with brutality inflicted by detectives, but it is hard to escape the conclusion that Jon Burge, a Chicago Police Department officer for three years at that point, had joined a force that sanctioned and willfully overlooked brutality.

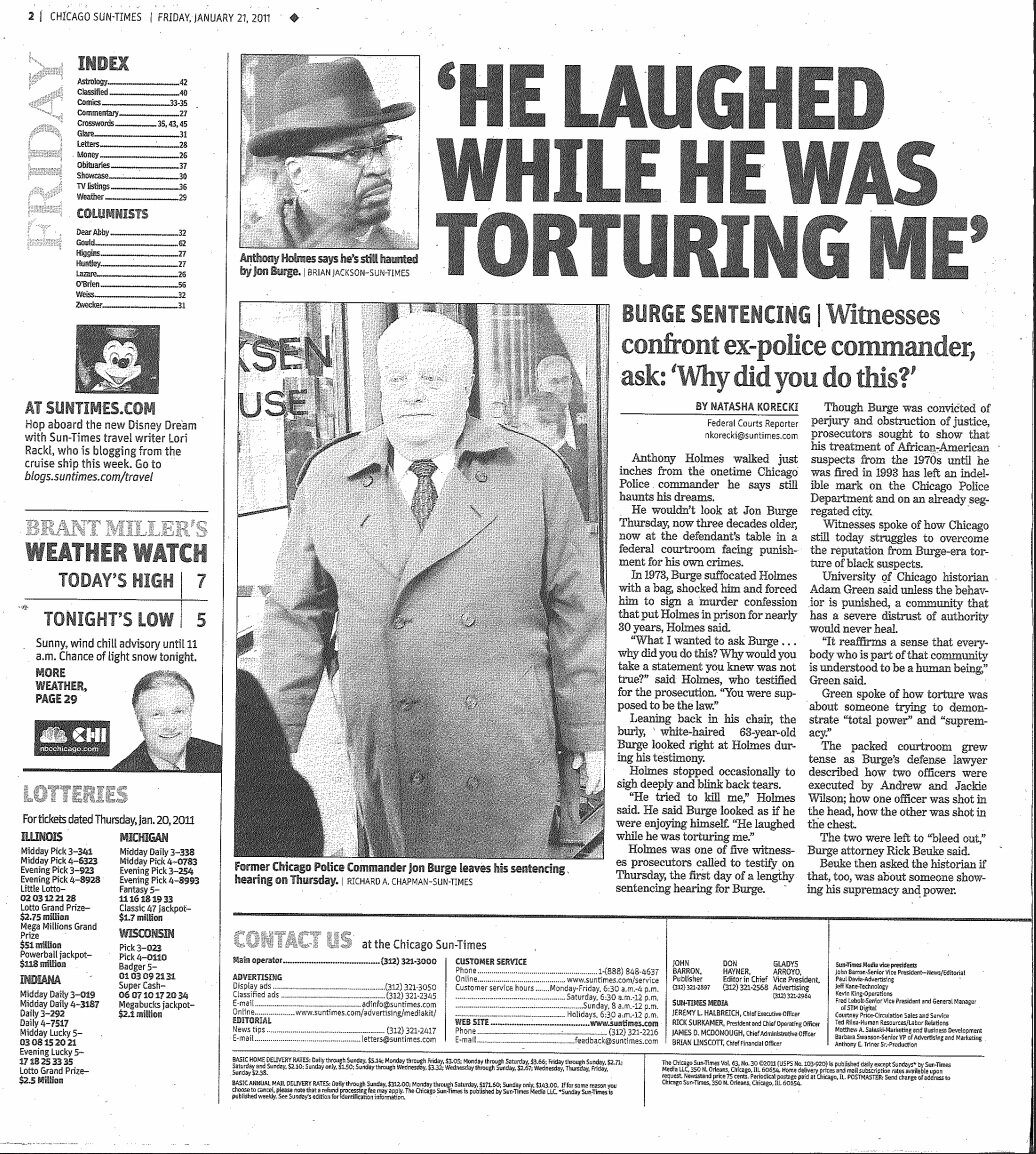

Burge simply had a different method of delivery. Five months before the Tribune series began, on May 30, 1973, the 24-year-old detective used electric shock to interrogate Anthony Holmes. In the Burge timeline, Holmes is not the first man abused, but he is the first we know of who was shocked in custody. Holmes’s complaint didn’t come to light until a civil suit, filed by Andrew Wilson, came to trial in 1989.

Wilson had been tortured with electric shocks from two different devices, burned against a radiator, kicked in the eye, and hit on the head with a gun after his arrest for killing Officers Richard O’Brien and Patrick Fahey during a traffic stop on February 9, 1982. Wilson emerged from police custody with better medical evidence of torture than any other victim, before or after, the most striking of which were scab marks in the shape of alligator clips on his nose and ears, parallel burns on his chest, and a large burn on his thigh. He was convicted of the double homicide, given the death penalty, and then awarded a new trial after the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the state hadn’t shown that his confession had been given voluntarily. He was tried again without the confession and convicted, but the jury gave him a life sentence, not death. Wilson then sued the city, the police, Commander Burge, and other detectives for the torture he’d been subjected to.

By that point, 16 years after the shocking of Anthony Holmes, the press and most of the city had not yet perceived that there was a pattern and practice of torture at Area 2. On February 9, 1984, both the Tribune and the Sun-Times had noted that Attorney Earl Washington, then representing Leroy Orange and Leonard Kidd, claimed that detectives had a shock device at Area 2, that it had been used on Orange, Kidd, and Andrew Wilson, that detectives targeted the genitals of suspects, and that use of the device was increasing. Neither paper investigated, and the story died.

On February 20, 1989, Chicago Lawyer editor Rob Warden, writing in Crain’s Chicago Business, revived the electric shock story, focusing on State’s Attorney Richard Daley’s lack of interest in the torture of cop-killer Andrew Wilson and the abuse of many South Side residents in the course of the Wilson manhunt in February, 1982.

The following month, as the Andrew Wilson civil suit was underway, the Chicago Lawyer published Mary Ann Williams’s article, “Torture in Chicago,” which described in detail what had happened to Wilson after his arrest for shooting Officers O’Brien and Fahey after a traffic stop on February 9, 1982.

I was covering that civil suit for the Chicago Reader. I had a certain advantage over the other reporters in the federal building: I was there for the one trial, while they had to cover the whole building. In another courtroom, sports agents Norby Walters and Lloyd Bloom were being prosecuted for fraud, racketeering, and conspiracy. It was a six-week long trial which featured a parade of star athletes and a member of the Colombo crime family, a silent partner of the agents, who had been useful in threatening athletes with getting their legs broken if they backed out of a representation agreement. (Bloom, a former nightclub bouncer, would be assassinated in his home in Los Angeles four years later.) So I understood the attraction. And viewed in the abstract, Andrew Wilson’s claims of electric shock machines deployed in a Chicago police station seemed highly unlikely -- that was something done in repressive, authoritarian countries, not in Chicago. Furthermore, Wilson had unquestionably killed two cops. He could not be expected to arouse the sympathy of a single juror. His suit seemed doomed from the start.

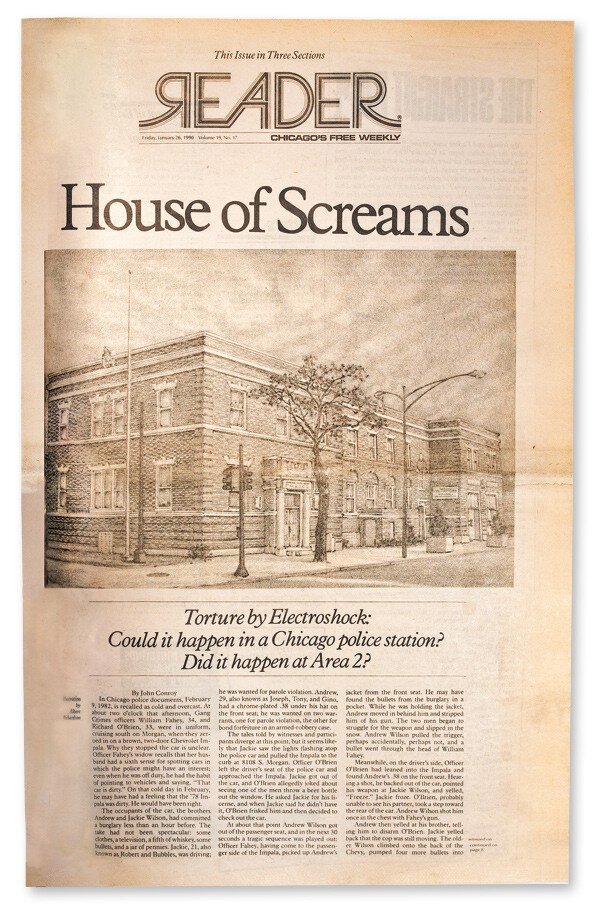

The Reader published my article, “House of Screams,” on January 25, 1990. I reported that the detectives’ defense had changed between the first trial, which had ended in a mistrial, and the second. In the first, police claimed that Wilson could not have been burned against a radiator because that particular radiator didn’t work, and a burn expert testified that the marks on Wilson’s body were abrasions, not burns. In the second trial, the police argued that the radiator did work and that Wilson had self-inflicted the wounds, and they produced a jailhouse informant to testify that Wilson had told him that he’d made up the whole torture story. The informant, a native of Liverpool had a lengthy record of fraud, theft, perjury, manslaughter, and blackmail. He had a criminal record in England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Hong Kong, and Monaco. His Interpol file warned that he was “Liable to commit theft and fraud.”

I also reported that anonymous letters in Chicago Police Department envelopes had been sent to Wilson’s attorneys at the People’s Law Office. Those letters, written by someone with an inside knowledge of the players at Area 2, indicated that the electrical devices did indeed exist and that they belonged to Commander Burge. This led Wilson’s attorneys to Melvin Jones, shocked during an interrogation nine days before Wilson’s arrest, and Jones led to Holmes and others who had been shocked. Over the course of some months, the PLO had compiled a list of eight men who had been tortured at Area 2. Over the next 20 years, that list would grow to more than 100.

In the three months following publication, we received four letters to the editor. Two writers were appalled by the torture, one was in favor, and one noted that it was an improvement over the days when such a suspect would have been executed on the way to the station. No one from the city denounced us. No one threatened a libel suit. No one said a word.

I hasten to add that even in the heyday of long-form journalism, the 19,900 word article was no doubt too long for many. And perhaps some didn’t trust it because it came from the alternative press, and others couldn’t believe or perhaps stomach it because it arose out of the case of a man who had killed two policemen.

Furthermore, this was before everyone had a video camera in his or her pocket, ready to record something that would contradict the police version of events. At that time, the default assumption in most of the city was that when police officers testified in court, they told the truth. The first DNA exoneration in the United States had occurred only five months earlier, and it had nothing to do with police misconduct, so the veracity of police testimony was yet to be undermined by that branch of science and the many exonerations it brought about.

However, the Chicago Reader, with a circulation of approximately 120,000, was a respected publication among the city’s journalists, and to us, this just seemed too important a story for the dailies to ignore. So my editor suggested we didn’t need any more Burge stories, and I understood completely. In those days, a Reader writer lived in dread of the capable staffs at the daily papers. If they got wind of what you were working on and thought it worthy, that piece you’d been sweating over for weeks or months would suddenly be somewhere else under someone else’s byline.

But the dailies didn’t pick it up, even after Burge was fired by the Chicago Police Board in February 1993. The Board’s decision was so vaguely worded that it was hard to pin down precisely what they thought had happened at Area 2, but it was clear that Burge had been fired over charges of torture, and the Tribune and Sun-Times ran headlines saying as much.

And yet neither of the dailies and none of the other media outlets then asked themselves about the victims of that torture, whose confessions were now certifiably suspect. Ten were on death row.

That, I think, was a reflection of the indifference of the community. Given the circulation of the daily papers and the reach of other Chicago media, it is safe to say that millions of Chicagoans now knew about the torture. And yet clergy, universities, bar associations, legislators (with a few exceptions), and community groups (again with a few exceptions) were not clamoring for an investigation. For more than a decade, the demonstrations that did occur were puny and easily ignored.

At the Reader, we revisited the torture story in 1996 and then repeatedly thereafter for more than a decade. In late 1998, the Sun-Times called for a judicial inquiry, and in July 1999, more than nine years after the torture became widely known, the Tribune did the same. All to little effect.

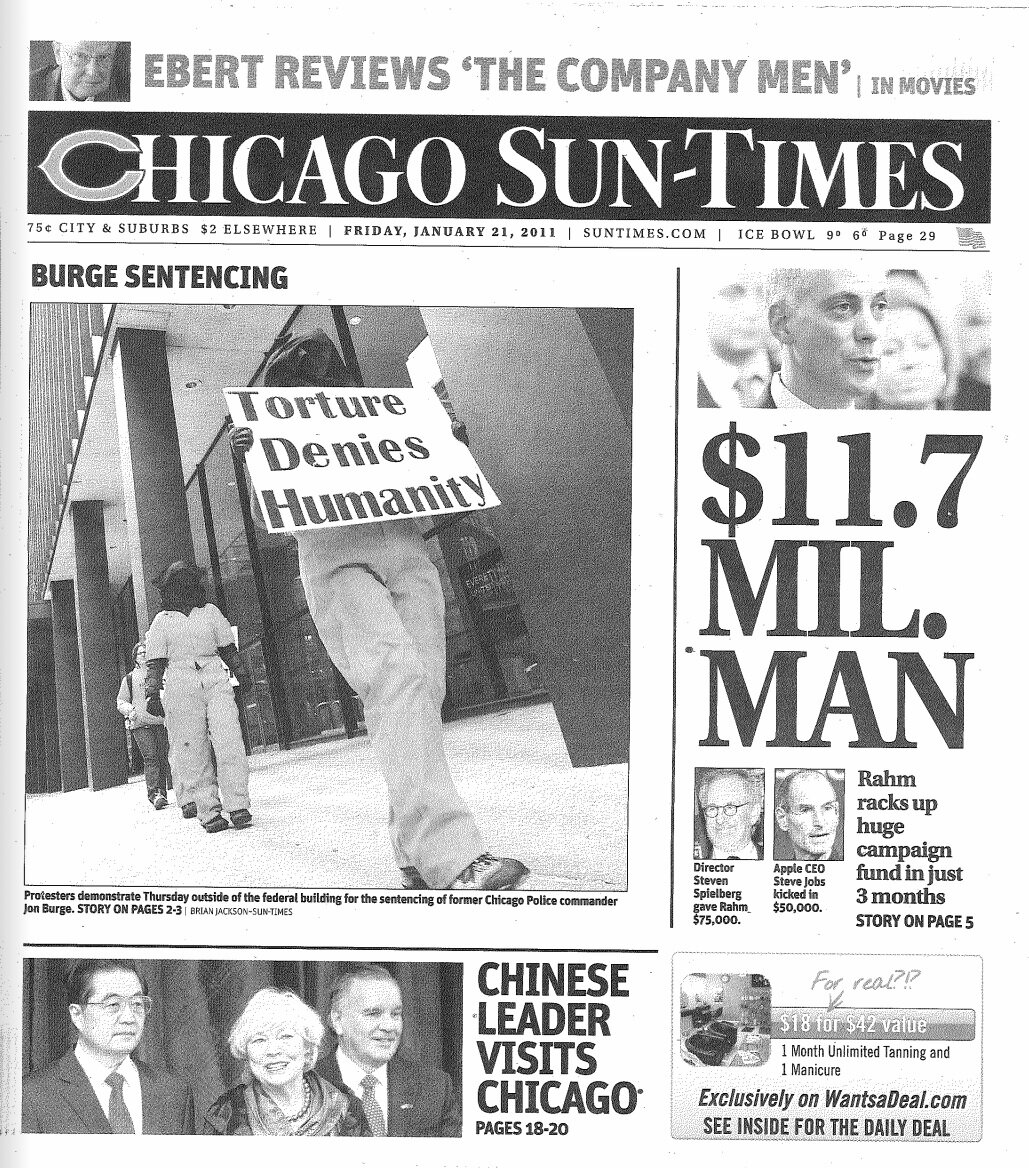

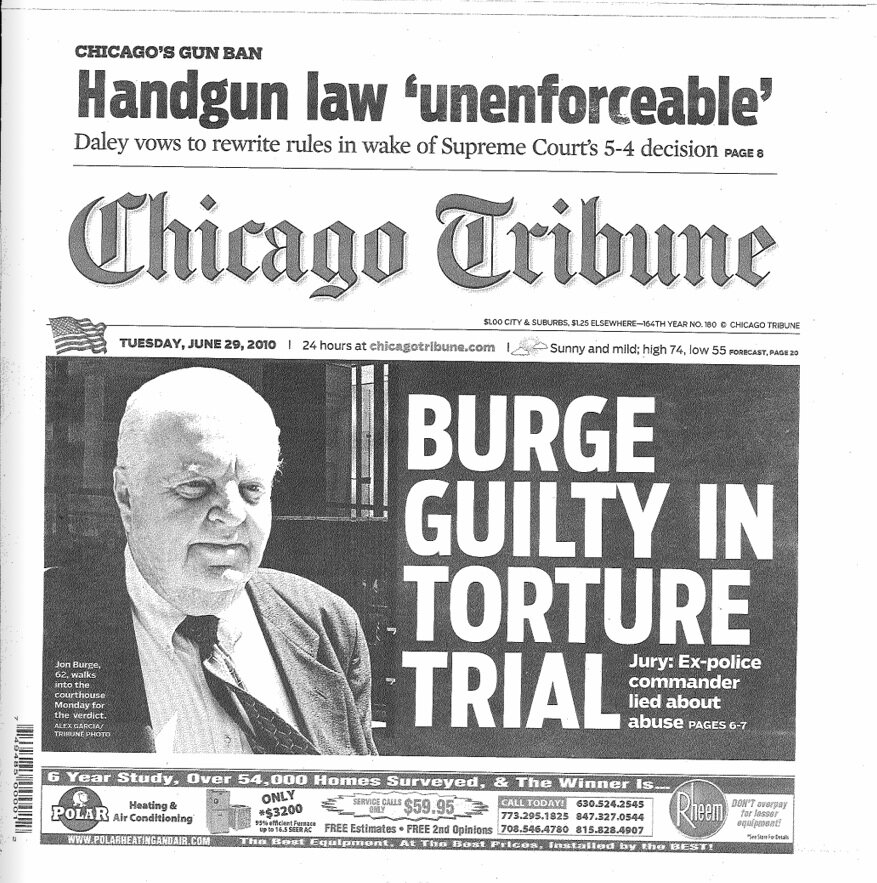

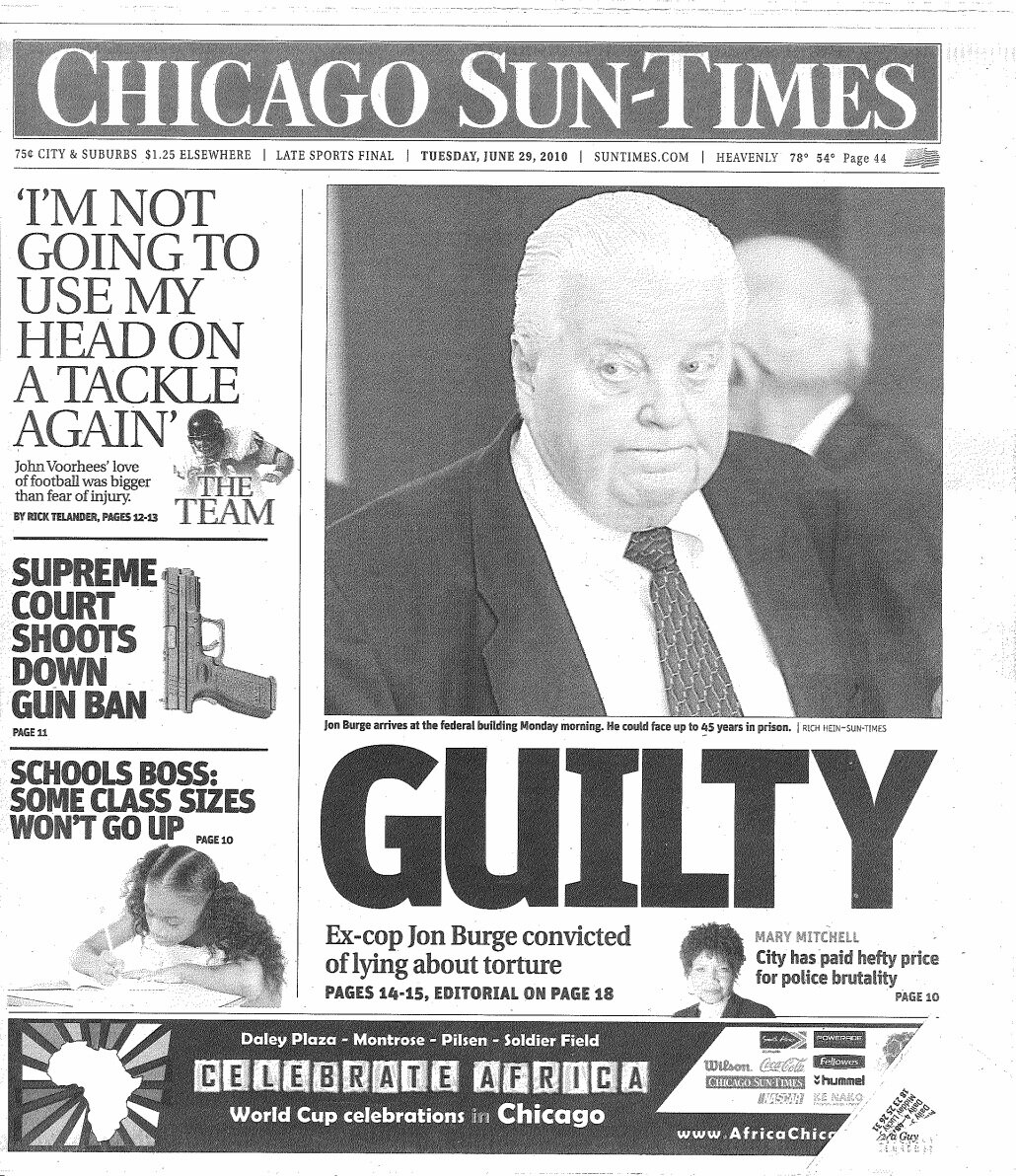

In October, 2008, Burge was indicted for perjury and obstruction of justice. He was convicted in 2010, 37 years after the electrical interrogation of Anthony Holmes and more than two decades after significant media attention began. No other officers have been criminally prosecuted.

In 2009, the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission was created to review the cases of people who claim to have been tortured. Some infamous detectives who served under Burge have since been named in more than 30 cases. The underfunded Commission meets five to eight times a year, sessions which are rarely attended by journalists from any of the major news outlets. The same is true of Chicago Police Board hearings, at which discipline is meted out for errant officers.

In Cook County, men walk out of prison exonerated on a regular basis, sometimes after more than 20 years in prison, and years later the city pays out millions of dollars when they prevail in civil suits, but full-scale investigations of the officers, prosecutors, and judges in those cases never follow.

— Written by John Conroy