Darrell Cannon was one of the first to be recognized by the court system as having founded claims of torture against detectives under the command of Jon Burge. Cannon served 24 years in prison for murder before being exonerated in 2004.

An appeals court decision in his case became a key touchpoint not only for his own eventual exoneration, but also for other Burge-related torture cases. Cannon’s appellate victory granted him a new trial, but he was again convicted at that second trial.

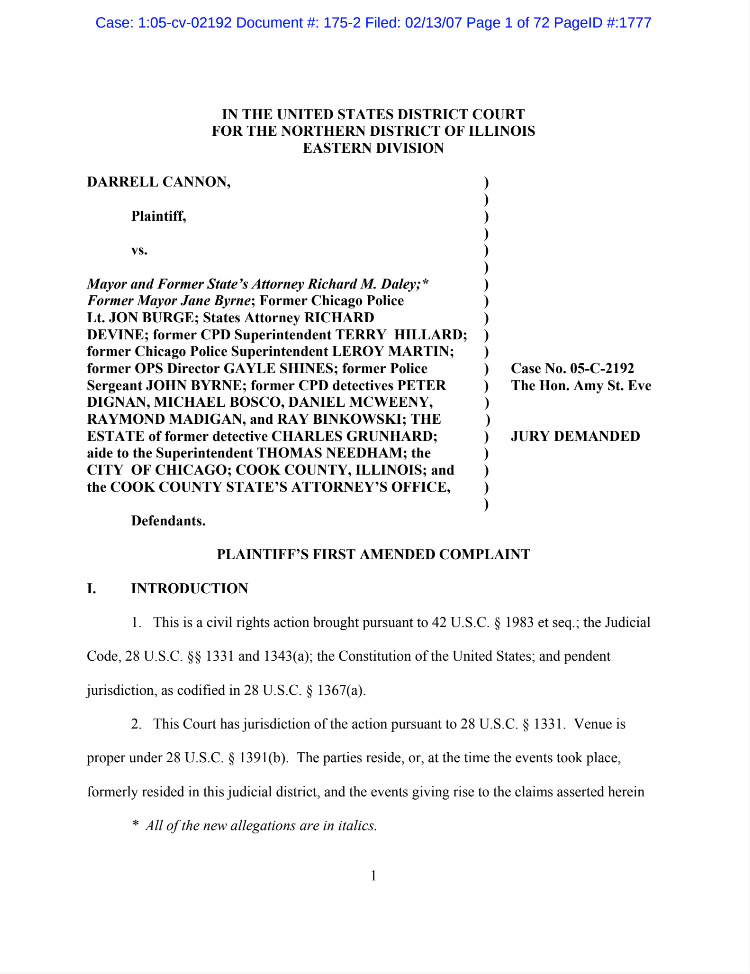

Even after his exoneration, the state parole board kept Cannon behind bars for three years before his release. Since, Cannon has become one of the most well-known advocates for the successful effort for reparations for torture victims in Chicago. Cannon and his attorneys at the People’s Law Office have continued to fight for him to receive fair compensation, which he has been denied because, courts have ruled, he already accepted a settlement in the 1980s that had netted him a total of $1,247.

A murder and an arrest

At the time of his arrest, Cannon, a general in the El Rukns street gang, was on parole for a previous conviction from 1971 for the murder of Emanuel Lazar. The murder charge, which came in his twenties, could have meant a life sentence. However, Cannon was paroled after 12 years in 1983.

Police allege 10 months later, on October 26, 1983, Cannon was driving with another gang member, Andrew McChristian, when he went to kill drug dealer Darren Ross. After Ross’s body was found buried at the Altgeld Gardens housing project, Andrew McChristian’s brother, Tyrone, implicated Cannon in Ross’s murder, police said.

Because police claimed Cannon had provided the gun and acted as the driver and instigator of the shooting, police charged Cannon with murder.

Cannon was awakened at about 6:30 a.m. on the morning of November 2, 1983, by Chicago police detectives. He was arrested by Sergeant John Byrne and Detectives Peter Dignan and Charles Grunhard of the Chicago Police Area 2 Violent Crimes division. He was then driven to a remote area of the South Side.

For the next eight hours, Cannon later said, the detectives proceeded to brutalize him.

Russian roulette and electroshock

Police coerced Cannon to confess to the Ross murder at a remote South Side location where detectives played a sadistic, terrifying game of Russian roulette with Cannon. An officer would show shotgun shells to Cannon and then turn around, looking as if he was loading the gun. One officer chipped Cannon’s front teeth and busted his lip as he shoved the gun in his mouth and forced Cannon to pull the trigger.

“You have to assume he did in fact put that shell in that shotgun,” Cannon told journalist Amanda Rivkin in an interview on June 26, 2016, remembering the torture. “My mind told me my brains was just blown out.”

Byrne pulled down Cannon’s pants and used a cattle prod on his testicles. “For me this was the most sadistic act ever performed,” he told Rivkin. “The feeling of it is something that is indescribable. I still live with it today.”

The officers soon took Cannon back to Area 2, where he was forced to sign a confession in the presence of Officer Daniel McWeeny and an assistant state’s attorney.

Complaints unheard and Cannon’s trial

Almost immediately after leaving police custody for Cook County jail, Cannon complained about the abuse and torture he had suffered under interrogation. Just five days after his arrest, Cannon’s wife lodged a formal complaint with the Office of Professional Standards (OPS), the internal investigatory board for Chicago police misconduct. The complaint was not sustained when the officers involved covered for each other and told OPS Cannon was lying.

At trial in 1984, Cannon unsuccessfully moved to suppress his coerced confession. Under oath, Byrne, Dignan, Grunhard, and McWeeny lied about torturing Cannon. On the basis of his confession, Cannon was convicted and sentenced to life.

Cannon told Rivkin that watching the officers testify to tell the truth and then lie was wrenching. “I’m often asked how do I feel about the detectives that tortured me,” he said. “And I would tell you that I hate the air they breathe. The hatred has never gone away.”

A long appeals road

In 1988, Cannon agreed to settle for $3,000 for the “nuisance value” that was offered by the Chicago Police and the city of Chicago for his claims of torture. In exchange, Cannon signed a release of his claims. After attorney’s fees and court costs, Cannon netted $1,247.70.

Meanwhile, Cannon appealed his conviction. While the Illinois Appellate Court did not agree to suppress his confession even though Cannon gave it under conditions of torture, the court did agree to give Cannon a hearing over the prosecution’s efforts to exclude African Americans from the jury at his trial.

At a retrial in 1994, Cannon was again found guilty.

A break in his case came in 1997, when an appeal’s court said Cannon’s involuntary confession was indeed relevant and he should be awarded a new trial.

Instead of a new trial altogether, Cannon and his attorneys agreed to a plea deal with prosecutors. He agreed to plead guilty to the lesser charges of armed violence and conspiracy to commit murder in exchange for a sentence of 40 years. (The plea was a so-called Alford plea deal, where the defendant admits a preponderance of evidence against him but not guilt). As the new sentence included credit for time served, it meant Cannon would be free by August of 2003.

However, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board (IPRB) had other plans. The IPRB ruled that because Cannon was on parole for the Lazar killing when his 1983 murder charge in the Ross case came, he was in violation of his parole and not eligible for release until 2064.

Cannon and his attorneys continued the fight for his release, and a successful lawsuit against the parole board secured his release.

Cannon was finally released on parole having served 24 years in prison, nine of which were spent in solitary confinement at the notorious super maximum security prison Tamms.

Activism after prison

Cannon has spent the years after his release fighting to see justice against Jon Burge and the other police officers who tortured him and others.

Cannon and his attorneys continued to fight for just compensation, trying to overcome the hurdle of his scant settlement in the 1980s.

Arguing before an appeals court in 2013, Cannon’s attorney Flint Taylor felt good about his chances when appeals’ court judges “upbraided” the attorney defending the city of Chicago, he wrote for In These Times.

As Taylor wrote in 2014:

[Judge Ilana] Rovner herself passionately rebutted the lawyer’s assertion that the police defendants simply denied that they tortured Cannon, stating that “they didn’t just ‘deny’—they lied, they cheated, they committed fraud, they committed cover-ups.”

“Here are the facts,” she continued. “These officers take a man with a prior murder conviction. Then they lie, then they torture him into making a statement that leads to a second murder conviction, then they lie about it, then they destroy evidence, then they engage in this incredibly lengthy cover-up with other city officials. You’ve got to help me. [On] [w]hat planet does he have a [fair hearing] in the courts under those circumstances?”

As the beleaguered city lawyer concluded his argument, Judge Sarah Barker, a former U.S. attorney from Indiana, focused on the insufficient settlement given to Cannon in 1988: “[G]iven all the things you know now and all the corruption that came to light … don’t you think that it’s a thin reed on which you’re attempting to hang your resolution to say, given all of that, $3,000 is a fair settlement?”

But the appeals court, in a “stunning” reversal, Taylor wrote, didn’t allow for a fairer settlement. “What the officers did to Cannon was unconscionable,” the court wrote. “The settlement was not.”

Freedom and reparations

Adjusting to freedom was often difficult, Cannon said in the 2016 interview. He kept tripping on carpet because he had become so used to concrete floors in prison. Regular food made him sick, as he was used to bland prison meals. “It’s been one hell of an adjustment,” he said.

Cannon was a part of the successful fight for reparations in Chicago in 2015, of which he received a portion. The reparations fight also included that his and other stories of torture would now be taught in Chicago schools.

“We did something here in Chicago that's never been done in America and that is saying something,” Cannon said of reparations. Referring to the Reconstruction promise of 40 acres and a mule after the end of slavery, Cannon said, “we’re still suffering, we’re still owed a great deal. But at least this is a stepping stone in Chicago. A grievous wrong was done to Afro-Americans under the color of law.”

He said in the interview with Rivkin, though, that the money was meaningless until all Burge torture survivors, many who remain incarcerated, are set free.

“The glass is only half full,” he said. “There’s still another half to go.”

—Written by Amanda Rivkin and Jeremy Borden

Documents

Media

Federal Appeal’s Court Rejects Torture Survivor’s Case. June 26, 2014. Attorney Flint Taylor writes for In These Times about Cannon’s case and an appeal’s court stunning decision in regard to Cannon’s civil settlement for just over $1,000.

Darrell Cannon: Surviving Chicago Police Torture. May 13, 2015. Cannon gives an account to the Praxis Center about what he endured at the hands of Chicago police.

Interview

June 26, 2016. Photojournalist Amanda Rivkin interviews Cannon.