Legal History

The People’s Law Office’s Archive

Excerpted from “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” by Joey L. Mogul. Public Interest Law Reporter Symposium, 2015.

From 1972 to 1991, over 110 Black men and women were tortured by former Chicago Police Cmdr. Jon Burge and a ring of white detectives under his command at Area 2 and 3 Police Headquarters in Chicago, Illinois. The torture techniques included electrically shocking men’s genitals, ears and fingers with cattle prods or an electric shock box; suffocating individuals with typewriter covers or plastic garbage bags; mock executions with firearms; beatings with telephone books and rubber hoses; and, in one instance, anally raping a man with a cattle prod.

In addition to inflicting excruciating physical pain, the detectives also routinely tormented the survivors with racist epithets and slurs throughout their interrogations. Darrell Cannon recounts that, throughout his interrogation, he no longer had a name and was only known as “nigger.” The electric shock box was commonly referred to as the “nigger box.” Detectives threatened to hang Gregory Banks, another torture survivor, “like other niggers” — making a clear reference to lynchings.

Burge and his men systematically engaged in acts of torture and racist verbal abuse to extract confessions, which were then introduced as powerful pieces of incriminating evidence at scores of survivors’ trials to secure their convictions and, in 11 cases, to obtain their death sentences. In the vast majority of these cases, the survivors complained about the torture and abuse they suffered at the hands of Burge and his men in their criminal proceedings, seeking to suppress their confessions on the basis that they were physically coerced in violation of their Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. In so doing, they courageously testified at hearings before judges and later before juries, laying bare the details of their painful, terrifying, humiliating and degrading interrogations. At each of these proceedings, the detectives routinely and cavalierly denied under oath that any torture or coercion occurred. Judges and juries routinely credited the word of white police detectives over those of Black torture survivors, facilitating the admission of these confessions in the criminal proceedings.

The first case: Andrew Wilson

The first case of torture that garnered significant publicity was that of Andrew Wilson. Wilson was accused of killing two white Chicago Police officers, William Fahey and Richard O’Brien, on February 9, 1982. Shortly after the police officers were shot on the street, the Chicago Police Department launched a vicious manhunt to capture those responsible, during which scores of African American homes on the South Side were ransacked, people were stopped and frisked on the street, and several young Black men were dragged into Police Headquarters and tortured to learn the whereabouts of the prime suspect, Wilson.

On February 14, 1982, Wilson was found, arrested and transported to Area 2 Police Headquarters where Burge and others handcuffed him across a hot radiator in an interrogation room. The officers then electrically shocked Wilson’s ears, lip, genitals, back and fingers with the electric shock box, causing him to flinch and sustain burns to his chest, thighs and chin from the radiator. The detectives also used a plastic garbage bag to suffocate him, beat him about the head and body, and burned him with a cigarette.

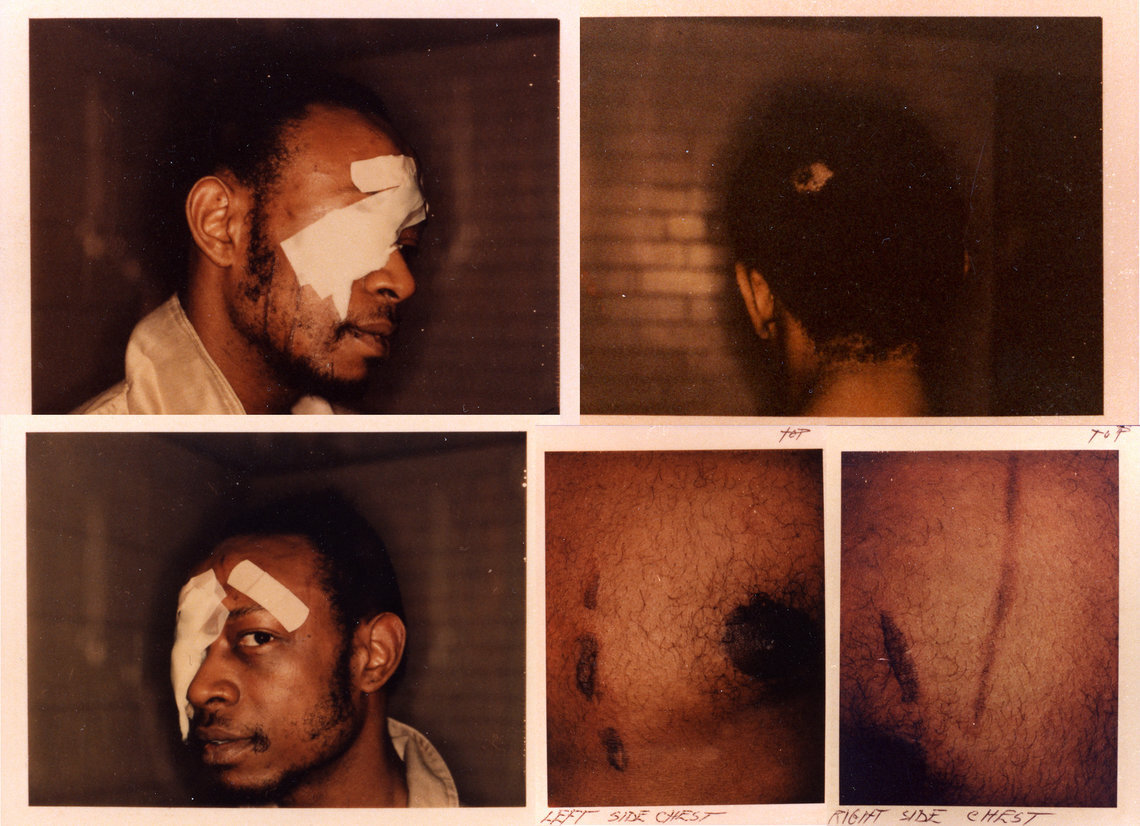

After Wilson confessed, he was transported to Cook County Jail where, for the first time since his interrogation, he received a full physical examination and medical treatment for his injuries. Dr. John Raba, the head of the medical unit, noted that Wilson sustained several physical injuries, including a battered right eye, bruises, swelling and abrasions on his face and head, and blisters on his right thigh, cheek and chest that were consistent with radiator burns. Unlike so many of the other torture survivors — whose torture was concealed by methods that intentionally left no marks — Wilson sustained visible injuries, providing irrefutable proof that he was tortured.

Troubled, Raba wrote the Superintendent of the CPD, Richard J. Brzeczek, demanding that Brzeczek conduct an investigation into Wilson’s allegations of electric shock and physical abuse. Brzeczek, in turn, wrote to the head of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office who, back in 1982, was Richard M. Daley, who later became Chicago’s longest-serving mayor. Brzeczek forwarded Raba’s letter to Daley and informed him that he would not conduct an investigation into Wilson’s allegations of torture and abuse unless advised to do so by Daley, expressing a desire not to interfere with Daley’s prosecution of Wilson for the murders of Fahey and O’Brien. Daley and his office never responded to Brzeczek’s letter, and neither Daley nor Brzeczek conducted an investigation into allegations of torture or the officers’ crimes. Instead, Daley and his staff repeatedly denied Wilson was tortured, successfully opposed his motion to suppress his confession and, in successfully doing so, used Wilson’s confession against him to convict him and obtain a death sentence. As a result of Daley and Brzeczek’s refusal to take any action whatsoever, at least 70 more Black men were tortured by Burge and men under his command over a 20-year period.

Wilson subsequently filed a pro se federal civil rights lawsuit seeking vindication for the torture he endured and sought the assistance of lawyers to represent him. Despite the unpopularity of Wilson’s cause, Jeffery Haas, John Stainthorp and Flint Taylor of the People’s Law Office (PLO) agreed to represent him. In the course of the civil litigation, the PLO received letters from an anonymous police source — subsequently dubbed “Deep Badge” — who disclosed a wealth of information about torture practices under Burge’s command at Area 2, including names of officers who engaged in torture, nicknaming them “Burge’s asskickers.” Deep Badge also identified Melvin Jones as a man who was tortured by Burge only nine days before Wilson’s interrogation.

Following Deep Badge’s leads, Haas, Stainthorp and Taylor tracked down 25 other Black men who alleged they were tortured at Area 2 Police Headquarters, confirming that Wilson’s torture was not an isolated incident, but simply one instance in a larger racist pattern and practice of torture. This was powerful evidence to corroborate Wilson’s allegations and that have been admitted pursuant to FED. R. EVID. 404(b) at his civil rights trial. The judge presiding over Wilson’s civil proceedings, however, would not admit this relevant and damning evidence. Instead, the judge allowed Burge’s defense counsel to present a slew of irrelevant evidence relating to the murders of Fahey and O’Brien. Consequently, Wilson did not prevail in the trial court.

Andrew Wilson

The Death Row 10

While Wilson was seeking to vindicate his rights in federal court, scores of Burge torture survivors were literally fighting for their lives behind bars. At the time of Burge’s termination from the CPD in 1993, there were 10 known Burge torture survivors on Illinois’ death row. These men were seeking relief from criminal convictions and death sentences in appeals and post-conviction petitions, arguing that there was a pattern and practice of torture within the CPD, citing Burge’s termination and the findings made in the Office of Professional Standards’ Goldston Report as strong corroboration of their allegations that their confessions were physically coerced. Yet, they were routinely denied relief by the Circuit Courts and Illinois Supreme Court, despite this new, game-changing evidence.

The men on the row were fed up with waiting for justice in the courts, and seeking to control their own lives and destinies, they courageously began to organize themselves by calling themselves “The Death Row 10.” The Death Row 10 urged their family members to attend court hearings and speak out on their behalf. They also wrote to organizers and activists beseeching them to stage teach-ins and protests about their cases and plight for justice. Aaron Patterson, one of the most prominent survivors on death row, boldly called and wrote to members of the press from his prison cell demanding the press report on his case and court proceedings and question Burge and the other officers responsible for the torture.

As the campaigns for the Death Row 10 and Patterson were gaining traction, the press was questioning the fairness and efficacy of the death penalty. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, 13 people sentenced to die were exonerated on the basis of innocence, leading then-Illinois Gov. George Ryan to issue a moratorium on all executions on January 31, 2000, becoming the first state in the nation.

As it was becoming increasingly clear that Gov. Ryan would not seek reelection in 2002, several lawyers representing capital defendants hatched a plan to seek clemency on behalf of all those on Illinois’ death row. The effort for clemency eventually became a highly visible public campaign, leading to over 200 public clemency hearings before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board where both family members of people on death row, including the Death Row 10, and family members of murder victims spoke on behalf of their loved ones. The hearings were emotionally charged and heartbreaking, as attention was focused on the flawed nature of the criminal legal system, including the role played by the Burge torture cases, while also exposing the wells of pain and loss among families of those no longer in the world. Ultimately, the campaign was successful.

On January 2, 2003, Gov. Ryan pardoned four of the Burge torture survivors — Madison Hobley, Stanley Howard, Leroy Orange and Aaron Patterson — on the basis of innocence. The following day, Gov. Ryan declared the death penalty was fatally flawed and commuted the death sentences of all prisoners then on death row.

It was another phenomenal victory for justice that did not come through the courts, but rather, was the product of extrajudicial actions by survivors, attorneys and activists in concert that later contributed to the abolition of the death penalty in Illinois in 2011.

As efforts to support the Death Row 10 were gaining momentum, it also became painfully clear that Burge and other officers guilty of torture enjoyed impunity for their crimes. While Burge was fired by the CPD, he retained his city-funded pension, and no other officer was terminated, let alone disciplined. Instead, many were promoted and allowed to retire with their full pensions intact.

In response to this injustice, I, as part of a group of death penalty attorneys who represented some of the Death Row 10, along with several organizers, started the Campaign to Prosecute Police Torture (CPPT). The goal of the campaign was to secure the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate and prosecute Burge and others. CPPT was well aware that the statute of limitations had expired for prosecuting any crimes of torture that the officers had committed but believed that the officers could and should be held responsible for their crimes of perjury and obstruction of justice for consistently denying that they engaged in acts of torture in ongoing court proceedings.

While the legal effort prevailed and Presiding Judge of the Cook County Circuit Court Criminal Division Paul Biebel Jr. granted the petition to appoint a special prosecutor, the campaign did not control who would be chosen as a Special Prosecutor. Two former Cook County Assistant State’s Attorneys who worked under Daley at the State’s Attorney’s Office, Edward Egan and Robert Boyle, were selected to lead the investigation into Burge and other detectives’ alleged crimes. After two years, it became apparent that their investigation was not going to lead to any indictments whatsoever.

Etchings made by Aaron Patterson on a bench with a paper clip in an interrogation room at Area 2 after he was tortured. These etchings served as his outcry in real time that he had been suffocated with a plastic bag and slapped to give a false confession.

The conviction of Jon Burge

In May 2006, the United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT) was evaluating the U.S. government’s compliance with the U.N. Convention Against Torture in Geneva, Switzerland. After two days of formal hearings with the U.S. governmental delegation and reviewing reams of reports and primary sources, the U.N. CAT issued a scathing indictment of the U.S. government’s failure to comply with the U.N. Convention Against Torture on May 19, 2006. In addition to calling on the U.S. government to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay and prosecute the chain of command at Abu Ghraib for crimes of torture, the Committee noted the “limited investigation and lack of prosecution” at Area 2 and 3 Police Headquarters, and it called on the U.S. government “to bring (the) perpetrators to justice.”

A month after the U.N. CAT issued its findings, the special prosecutors concluded their investigation, finding that Burge and other detectives under his command committed crimes of aggravated battery and armed violence, surprising no one. However, the special prosecutors claimed they could not prosecute Burge and others because the statute of limitations had expired — not only on these physical violations, but also on the crimes of perjury or obstruction of justice for repeated false testimony denying the acts of torture. To briefly summarize the results of their four-year, $7 million investigation, it was too bad, so sad, time to close the book on this unfortunate story.

Torture survivors, their family members, CPPT and other activists and attorneys refused to take no for an answer. Organizations, including Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT), marched in the streets and held rallies at Daley Plaza. We convened a hearing at the Cook County Board and obtained the passage of a resolution calling on the U.S. Attorney’s Office to prosecute Burge and his men for the crimes they committed. Others organized a letter writing campaign and petition drive demanding that the U.S. Attorney in the Northern District of Illinois bring charges against Burge.

A year and half after the U.N. CAT issued its findings, Burge was indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the Northern District of Illinois and U.S. Department of Justice for two counts of perjury and one count of obstruction of justice for falsely denying he and others engaged in torture in a civil rights case.

On June 28, 2010, after torture survivors Anthony Holmes, Melvin Jones, Shadeed Mu’min and Gregory Banks courageously testified against Burge, Burge was found guilty of all three counts, and in January 2011 he was sentenced to serve four and half years in prison.

While Burge’s conviction was significant, the victory was a hollow one. Burge’s conviction failed to address the material needs of the torture survivors. Many of the survivors continued to suffer psychologically from the torture they endured, experiencing flashbacks and nightmares of their interrogations, but there was no place for them to obtain any psychological counseling or assistance. Moreover, the vast majority of torture survivors, including Holmes, Jones and Mu’min, had no legal recourse to seek any financial compensation or redress. The statute of limitations on any civil claims they could have brought expired decades ago, as many languished in their prison cells fighting their criminal prosecution and convictions. As BPAPT argued in 2008, the Burge torture survivors were entitled to reparations.

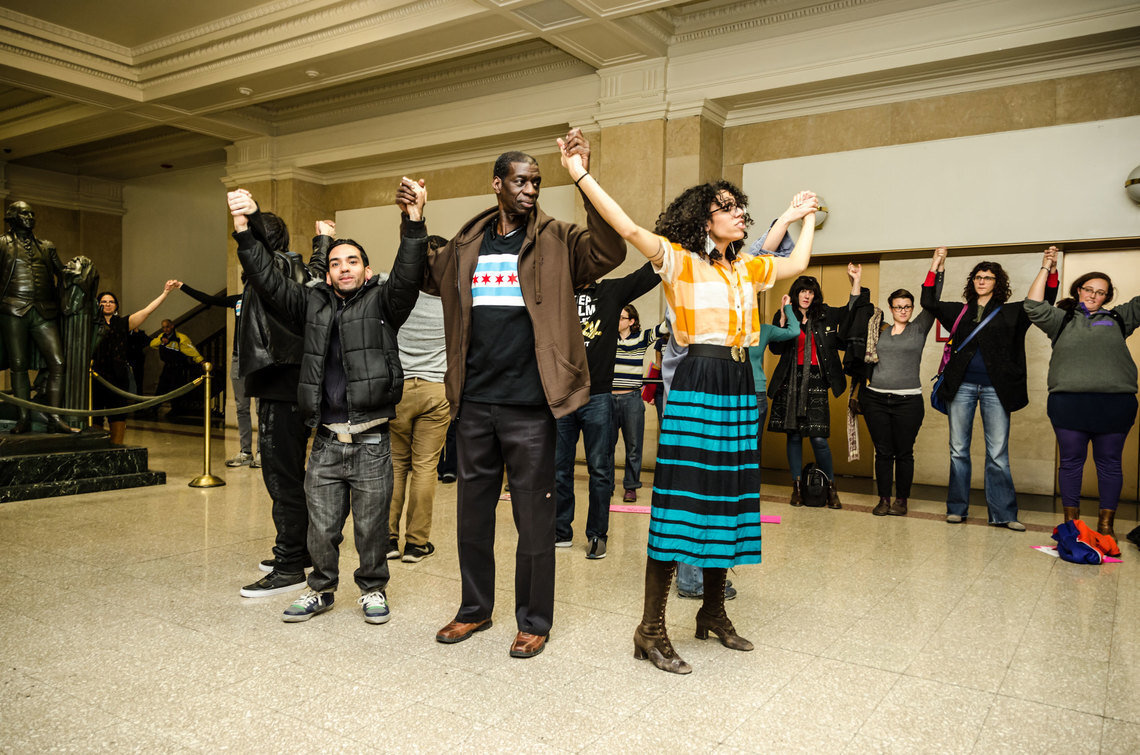

Reparations Coalition at City Hall, photo credit: Sarah-Ji Rhee

Reparations and the ongoing legal battle

In 2015, the legislation that passed as a result of the Reparations Coalition organizing provided for the creation of a $5.5 million reparations fund to pay up to $100,000 to each eligible Burge torture survivor still alive; the provision of counseling services to police torture survivors and family members at a dedicated facility on the South Side of Chicago; free tuition at Chicago’s City Colleges for Burge torture survivors and their family members, including their grandchildren; job placement for Burge torture survivors in programs for formerly incarcerated people; priority access to the city of Chicago’s reentry support services, including job training and placement, counseling, food and transportation assistance, senior care, health care, and small business support services; a formal apology from the mayor and City Council for the torture committed by Burge and his men; a permanent public memorial acknowledging the torture committed by Burge and his men; and a history curriculum on the Burge torture cases to be taught to all Chicago Public School students in the eighth and tenth grades.

Throughout the continuing saga of the Chicago police torture cases, the legal system failed the survivors and community every step of the way. The courts failed to stop Burge and others from torturing Black men and women for decades, or prevent the use of their coerced confessions to obtain wrongful convictions. State and federal prosecutors failed to hold Burge and other detectives fully accountable for their crimes and international human rights violations. The civil legal system was not designed to provide, and is therefore incapable of providing, the holistic redress needed by all of those harmed by Burge and his men.

While lawyers and legal workers played an indispensable role in these cases, zealously advocating for their clients and using both the criminal and civil cases to investigate and document the torture practices and those harmed, the courts were not the vehicle that yielded the measure of justice achieved in these cases. Lawyers could not have litigated this to success. It was the power of the people — torture survivors, family members, organizers, activists, lawyers and legal workers — that made the dream of reparations into a reality.

— Written by Joey L. Mogul

Joey Mogul, a partner at the People’s Law Office and organizer of the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM), has successfully represented several Chicago Police torture survivors in criminal post-conviction proceedings and in federal civil rights cases since 1997. Mogul served as co-lead counsel in litigation securing legal representation for the Burge torture survivors who remain behind bars in post-conviction proceedings in 2014. Mogul also successfully presented the cases to the U.N. Committee against Torture (CAT), obtaining a specific finding from the CAT calling for the prosecution of the perpetrators in May of 2006. Mogul drafted the original City Council ordinance providing reparations for the Chicago Police (Burge) torture survivors filed in October of 2013 on behalf of CTJM.