On September 11, 2013, the Chicago City Council approved settlements of $6.15 million each in wrongful conviction lawsuits by Marvin Reeves and his fellow torture victim Ronald Kitchen.

Later the same day, Mayor Rahm Emanuel issued the city’s first official apology for a 40-year history of torture and coverup, most notoriously by former Cmdr Jon Burge and his detectives, calling it “a stain on the city’s reputation.”

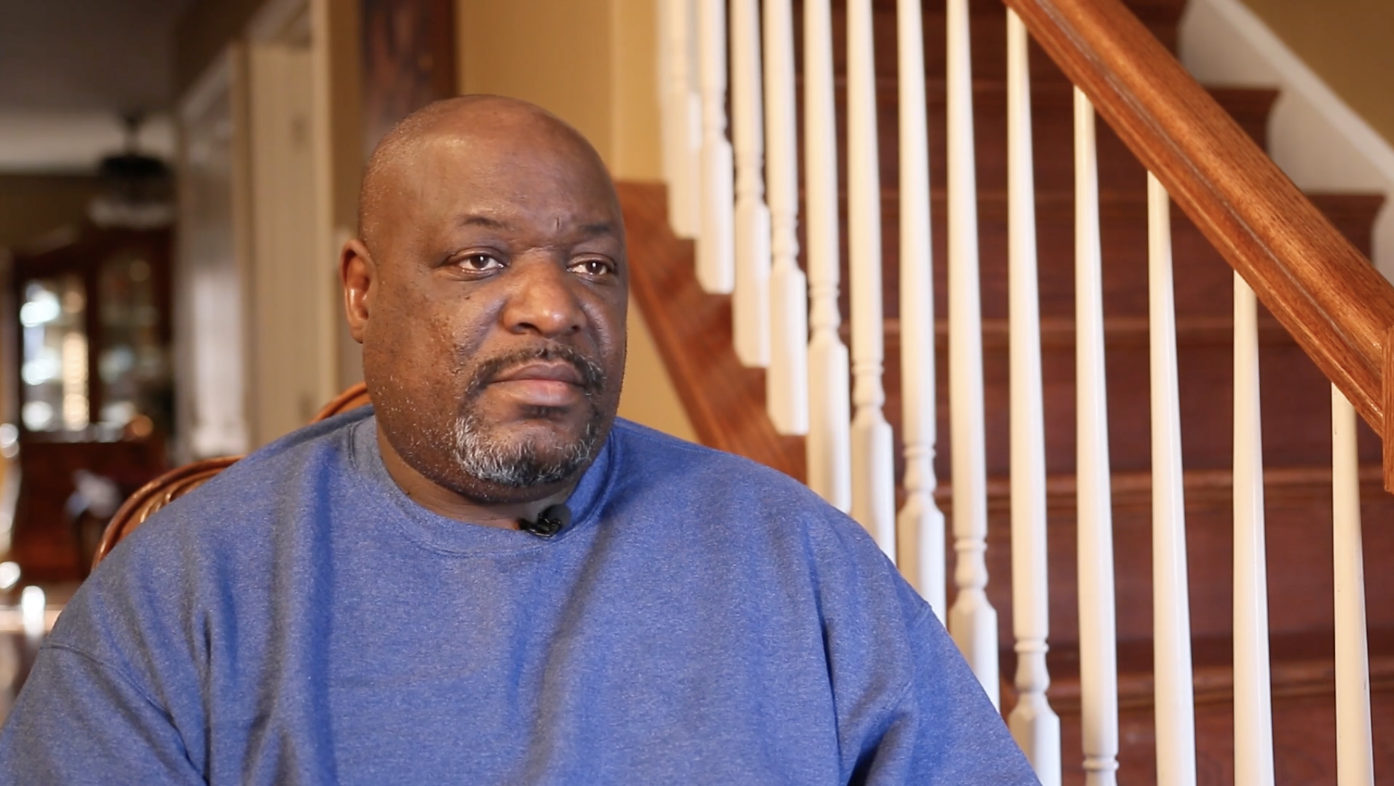

Reeves’ ordeal began on August 26, 1988. At the time he was a 29-year-old father, an alley mechanic and sometime tow truck driver, living on the South Side with his girlfriend, who was pregnant with a son who Reeves wouldn’t see for two decades. “I found I was able to make honest money, pay my bills and feed my kids,” Reeves said in an interview with the Invisible Institute in 2017. “It was an honest job that paid an honest dollar.”

A month earlier, the bodies of two women and three children had been found in a burning home on the South Side. The crime was widely covered, and media published a phone number to call with information, along with notice of a $2,000 reward for information.

A prison inmate named Willie Williams called police, first asking them to help get him work release and then claiming that Ronald Kitchen had told him in two phone calls that Kitchen and his friend Reeves had committed the murders in retaliation for an unpaid drug debt.

Police obtained a court order allowing them to eavesdrop on Williams’ calls to Kitchen and Reeves, and he called the two men 36 times in mid-August but never elicited any incriminating information.

Kitchen was arrested on August 25 and taken to Area 3 Detective Division, where Burge was the commander. According to court filings, Burge and Detective Michael Kill beat and kicked Kitchen in the head, upper body and groin for several extended sessions. Another detective slammed him in the head with a phone when he asked to call an attorney. In another interrogation, he was hit in the head with a phone book and in the groin with a blackjack.

After 16 hours of abuse, Kitchen signed a confession in which he implicated Reeves. At Kitchen’s first court hearing he reported his abuse, and a judge ordered him transferred to a hospital. A physician at Cermak Hospital later testified that Kitchen’s “testicles were swollen and tender to the touch,” and Kitchen was treated for testicular trauma.

Reeves was arrested on August 26. He recalls that he was in bed asleep when officers banged on the door and “literally kicked the door off the hinges.” They “ran in the house. ... (An officer) put a gun to my head, and then his exact words were, ‘Nigger, if you move, I’ll blow your brains out.’”

“(They) put me in a room, handcuffed me to the wall, and one officer after another came in there kicking and beating on me. (Saying) this is what we do to guys that like to kill women and kids. And that went on for several hours.”

After he was held for a period and taken downtown for a polygraph test, Reeves said, detectives “put me in a room, handcuffed me to the wall, and one officer after another came in there kicking and beating on me. (Saying) this is what we do to guys that like to kill women and kids. And that went on for several hours.”

Reeves never confessed. Confronted with a statement and demands that he sign it, he recalled a warning from his mother when bill collectors would come to their house. “She said one of these days you’re going to sign your life away, by signing stuff and not reading it. And I read it because I heard my mother's voice. When I read that paper, (it said) I went over there to kill those people for (a) $1,250 (debt). Are you serious? Two women, three children, $1,250? Never in a million years.”

Kitchen was tried in 1990, convicted and sentenced to death.

Reeves was tried in 1991 for the quintuple murder on the basis of Williams’ testimony and Kitchen’s coerced confession. Shortly before his trial — too late for his defense to investigate further — prosecutors turned over police reports showing that police had evidence that pointed to the husband of one of the murder victims, his brother, and a romantic rival. The husband had been seen at the victim’s house on the day of the murder, and all three had failed polygraph tests regarding their involvement in the crime. Police had ignored this evidence and focused solely on Reeves and Kitchen after Williams contacted them.

Reeves was convicted by a jury on May 28, 1991, and sentenced to life in prison. That conviction was reversed on a legal technicality by the Illinois Appellate Court in 1995, and Reeves was retried and convicted again in 2000.

While Reeves’ case was winding its way through the court system, awareness and acknowledgment of torture by Burge and Chicago police under his command were slowly gaining momentum. The Chicago Police Board fired Burge in February 1993, a year after a federal judge ordered the release of a 1990 report by CPD’s Office of Professional Standards. The OPS report, kept secret for two years, found “systemic” and “methodical” abuse of suspects by Burge and his detectives, including “planned torture.” In 2003, Gov. George Ryan pardoned four Burge victims who were on death row and went on to commute all death sentences, including Kitchen’s, to life without parole.

In 2002, Presiding Judge of the Cook County Circuit Court Criminal Division Paul Biebel Jr. granted a petition by civil rights groups seeking a special prosecutor and appointed two former assistant state’s attorneys to investigate charges of torture by Burge and his detectives. Their report was issued in 2006. They found evidence of police abuse beyond a reasonable doubt in only three cases, and concluded that due to the statute of limitations, there were no grounds to prosecute Burge and others. (That conclusion was proven wrong when federal authorities successfully prosecuted Burge for perjury and obstruction of justice in 2010.)

In Reeves’ case, they cited minor differences in his recollections of events over a period of years to conclude his allegations of abuse lacked credibility. A “shadow report” by civil rights lawyers and community activists subsequently charged that the special prosecutors “conducted an investigation that was hopelessly flawed and calculated to obfuscate the truth about the torture scandal,” and that they “unfairly evaluated the credibility of the alleged torturers and their victims.”

In 2003, Judge Biebel granted another petition citing conflicts of interest in the state’s attorney’s office and named the Illinois attorney general’s office to represent the state in post-conviction petitions by individuals alleging torture. A few months later the attorney general’s office decided it would reinvestigate the cases against Reeves and Kitchen. The office also turned over to defense lawyers files from the state’s attorney showing coordination of sentencing and financial benefits for Williams by prosecutors in Kitchen’s and Reeves’ trials.

Defense lawyers asserted that this new evidence seriously undermined the credibility of Williams’ testimony, which along with Kitchen’s coerced confession was the only evidence against Reeves and Kitchen. At trial Williams had testified that he had received no benefits in exchange for his testimony, and Assistant State’s Attorney John Eannace had repeated Williams’ statement in closing arguments. It turned out that Williams, who had served just one month of a three-year sentence for a burglary conviction when he contacted police in August 1988, was released from prison on a work-release program in October of that year, long before the trial took place. Eannace was the state’s attorney who arranged for that release. In addition, Eannace had filed requests for housing assistance for Williams, which he received after he was released.

Defense attorneys also developed evidence that the phone calls in which Williams claimed Kitchen initially confessed and implicated Reeves could not have happened. Williams had repeatedly stated that he made two collect calls to Kitchen’s residence. When he was confronted with phone records showing Kitchen’s residence was never billed for those calls, he changed his story to say he made third-party billing calls, requesting that another line be charged for the calls. Lawyers showed that phone company policy at the time prohibited operators for charging calls from correctional institutions to anyone but the recipient.

Post-conviction proceedings for Reeves and Kitchen were put on hold while the special prosecutor’s investigation was underway. It took three years after that — despite mounting evidence of the two men’s innocence — for the attorney general to agree to drop charges against them. They were released from prison, after 21 years behind bars, on July 7, 2009, and six weeks later Judge Biebel granted the two men certificates of innocence.

“When you come from captivity and are thrust into freedom, it’s a shock. You almost forget how to survive in the free world.”

Adjusting to life on the outside was difficult for Reeves. Venturing into the neighborhood, simple things like buying a snack at a McDonald’s seemed overwhelming. “When you come from captivity and are thrust into freedom, it’s a shock. You almost forget how to survive in the free world,” he recounted in an interview with Life After Innocence, an organization that helped him with reentry. He had difficulty obtaining a driver’s license, and trouble finding a job. “Even though I’m exonerated, employers fear me because I spent 21 years in prison,” he said at the time.

The legal settlement afforded him a degree of security and enabled him to revive his interest in cars: he now owns several. But “if there ever was a time when somebody walked up to me and said, ‘Marvin, give it all back, we’re going to put you back in 1988,’ I’d jump at the chance.”

“The long years of incarceration, of not being there for your family — it never goes away. It’s always there.”

The disadvantages his children suffered while he was in prison are a constant reminder of the injustice of his wrongful conviction, Reeves told the Invisible Institute. “The long years of incarceration, of not being there for your family — it never goes away. It’s always there.” But his “deep-rooted religious family,” which supported him through his years in prison, remains a source of strength for him.

Reeves said he’s seen firsthand how the system works — “how they work to convict innocent people, how they cover up for their own. You know it’s just not right....Because crooked cops that don't care to do their job. Crooked prosecutors that are overzealous don't care, because they get a pat on the back when it's a high The long years of incarceration, of not being there for your family — it never goes away. It's always there. Bring somebody in, get a conviction, you get a pat on the back. But what about 20 years later when you find out that actually it was the wrong guy? Do you still pat this guy on the back? Because he did an injustice?”

Asked what he would want people to know about police torture in Chicago, Reeves said, “I would want the public to know that it did happen. This ain’t no fairy tale. This ain’t something that some people made up out of la-la land. These are true facts, and we are real people.”

— Written by Curtis Black