Activism

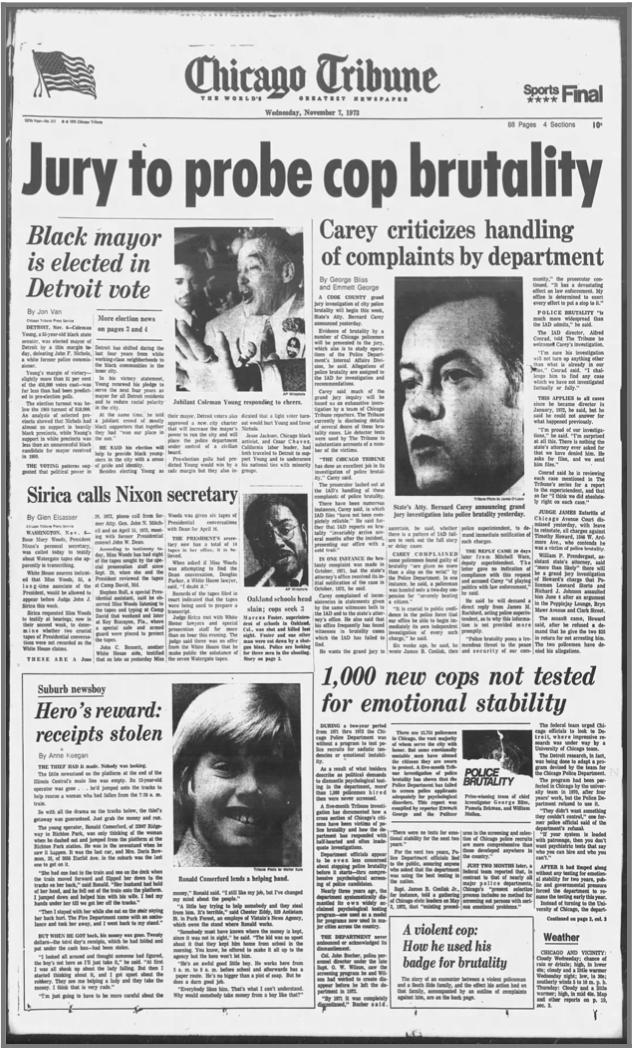

Four Decades of Struggle in the Jon Burge Torture Cases

On May 6, 2015, the city of Chicago passed unprecedented legislation providing reparations to Black people tortured by former Chicago Police Cmdr. Jon Burge and a ring of detectives under his command. This historic moment was the culmination of a 40-year struggle that involved decades of litigation, organizing and investigative journalism. The Reparations legislation is the product of a grassroots effort that boldly dared to imagine, struggle for and win a holistic package of relief that far surpassed remedies available through the U.S. civil legal system. Organizers insisted that the city of Chicago be held accountable for the harm that had been inflicted on torture survivors by providing a holistic reparations package that included:

What Reparations Looks Like for Burge Police Torture Survivors: education on police torture in public schools, formal apology from Chicago city council, free college education for survivors & their families, $5.5 million in financial compensation, public memorial to torture survivors, a counseling center for Burge torture survivors. Credit: Amnesty International

The struggle is ongoing. There are survivors of torture at the hands of Cmdr. Burge’s crew and other Chicago police who are still incarcerated, who are still fighting to overturn their convictions and be freed. The sole remaining component of the reparations package that has yet to be fulfilled is the creation of the public memorial that honors the survivors, acknowledges the violence they suffered at the hands of the police, and memorializes the struggle for justice waged over decades. Members of Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM), the group that initiated the 2015 reparations legislation, have been steadfast in their commitment to bring the memorial to life, and through a juried process, a design for the memorial titled Breath, Form & Freedom has been selected. But as of February 2021, survivors are still waiting for the Lightfoot administration and City Council’s promise to make good on the city’s promise to build the memorial.

Architectural renderings of Chicago Torture Justice Memorial, proposed design as of February 2021. Courtesy CTJM

There are many morals to the story of the four-decades-long odyssey seeking justice on behalf of the torture survivors and their family members. One is that the legal system failed the survivors, Black communities and the pursuit of justice time and time again. Another is a lesson about building power, and how attorneys and legal workers can work with, alongside, and in support of people directly impacted by the criminal legal system to achieve a measure of justice and accountability our legal system is incapable of providing.

— Alice Kim, director of Human Rights Practice, Pozen Family Center for Human Rights at UChicago, & co-founder of Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, and Joey Mogul, partner at People’s Law Office, initiator & co-founder of Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, and author of the reparations ordinance.

> Preface: Lessons from the Fight for Reparations

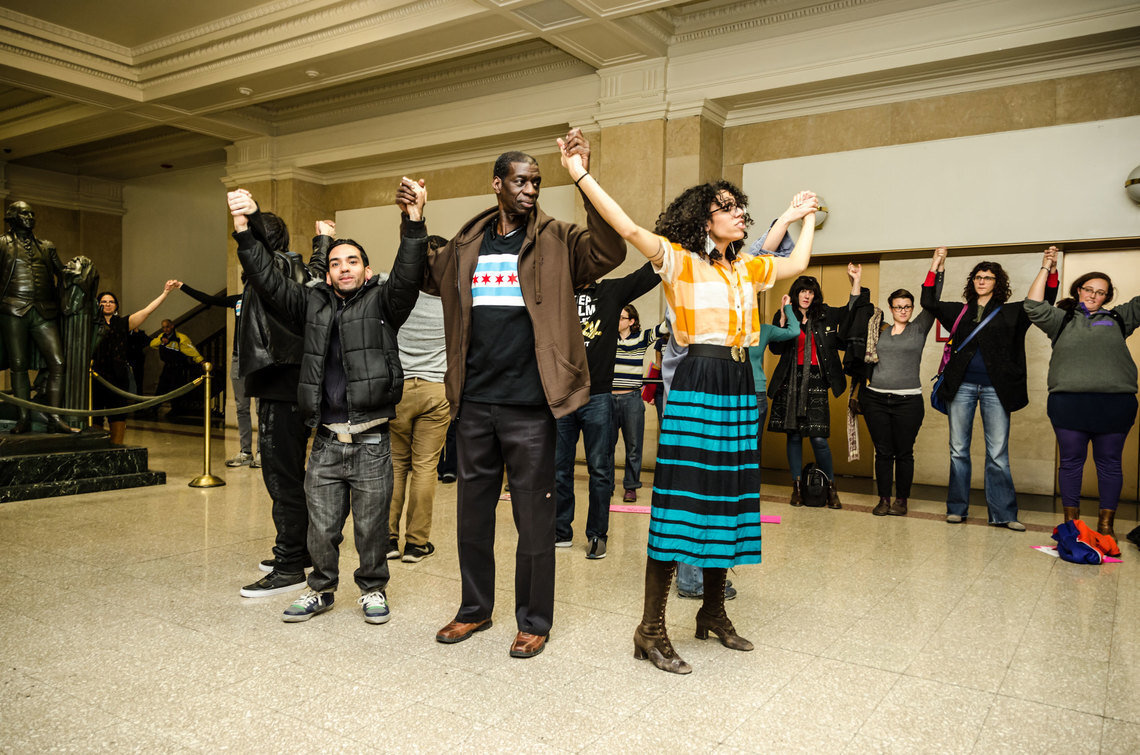

On May 6, 2015, 14 torture survivors – all African American men – stood up at the Chicago City Council meeting as their names were read aloud by Alderman Joe Moreno, a chief sponsor of the Reparations Ordinance for Chicago Police Torture Survivors. Each one of these men had been tortured by former Cmdr. Jon Burge or officers under his command; many had languished behind bars, incarcerated for decades as a result of confessions elicited by torture. As the City Council unanimously passed a reparations package for Burge torture survivors, they received a long overdue apology from Mayor Rahm Emanuel on behalf of the city and a standing ovation from the City Council.

For Anthony Holmes this moment was a long time coming. He had fallen prey to Burge in 1973 in an interrogation room at Area 2 Police Headquarters on the South Side of Chicago. There, Burge repeatedly electric-shocked him and suffocated him with a plastic bag. Holmes eventually confessed to a crime he did not commit, and his confession, the only evidence against him, was used to convict and sentence him.

“What really hurt me is that no one really listened to what I had to say,” Holmes testified at Burge’s sentencing hearing in 2011. “No one believed in me.” Forty-three years after Banks had been tortured, the city of Chicago finally began a process to make amends.

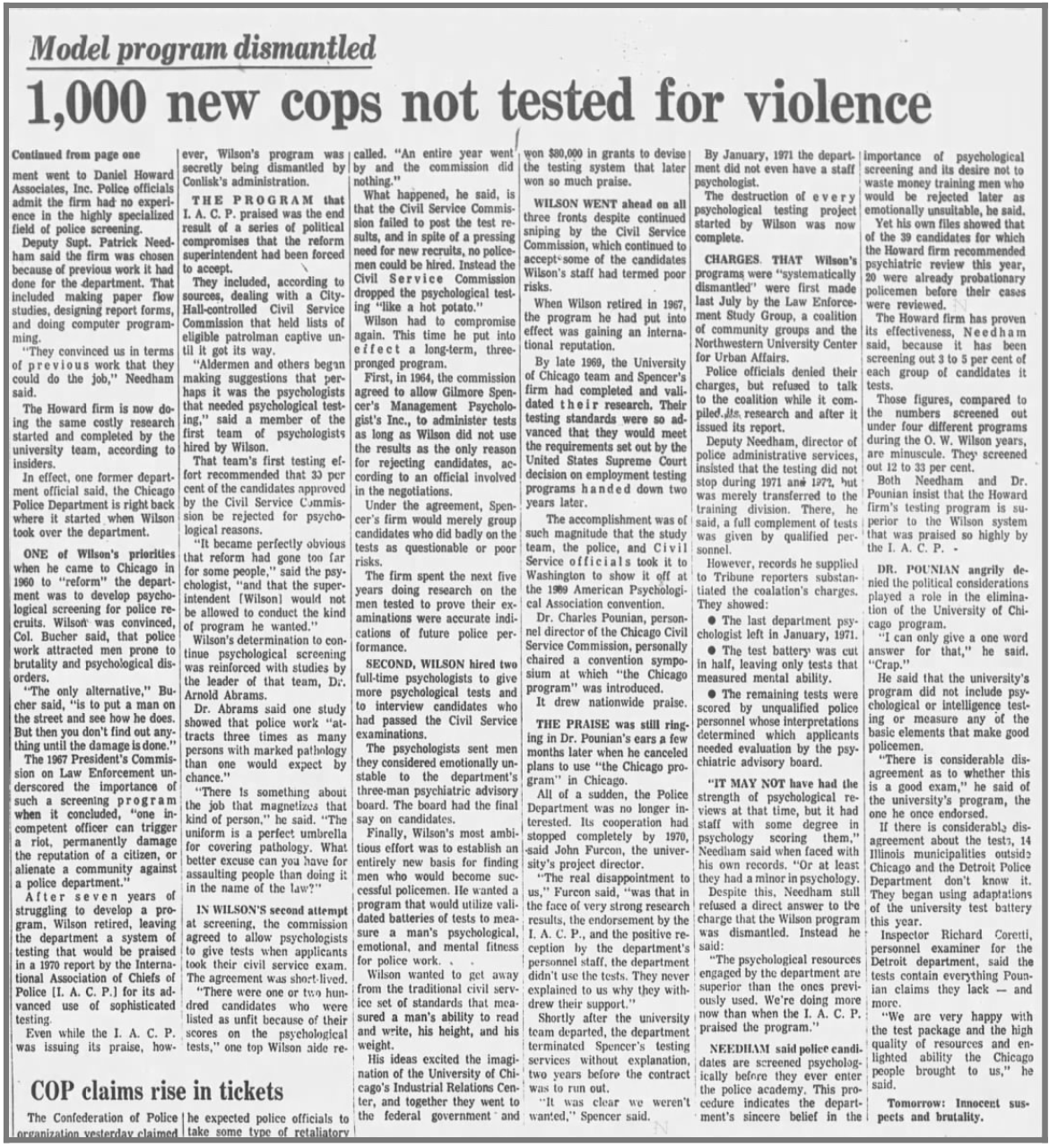

I witnessed this historic moment in City Council chambers along with hundreds of activists and family members who had participated in countless protests, marches, rallies, teach-ins, sing-ins, Twitter power hours and train takeovers over the prior six months. One of these activists was Mary L. Johnson, whose son Michael Johnson was tortured by Burge in 1982 and is currently serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole (for an unrelated conviction). She was one of the first people to file a complaint against Burge, and for more than three decades she has been unceasing in her efforts seeking justice for her son and all Chicago police torture survivors. Along with a group of intrepid mothers who have been the heart and the backbone of the movement, Johnson’s steadfast activism helped pave the way for the campaign that successfully organized and won reparations.

In the midst of a hotly contested mayoral election and an unrelenting campaign led by Burge torture survivors and a coalition of activists — including Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, Project NIA, We Charge Genocide, and Amnesty International USA, with critical organizing efforts from Black Youth Project 100, the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, Chicago Light Brigade and others, Chicago evolved from a city that had covered up the systematic torture of African Americans by white officers — 125 fully documented cases — into one taking unprecedented measures of redress for Burge torture survivors. This was the result of struggle and coalition work, not the benevolence of politicians.

When Chicago passed reparations legislation, it marked the first time in U.S. history that a municipality was providing reparations for racially motivated police violence. In 2006, human rights attorney Stan Willis founded Black People Against Police Torture to galvanize the support of the Black community, and Willis and BPAPT made the initial demand for reparations to heal the long-term trauma of torture for individuals and their families. Introducing the language, demand, and possibility into the political vernacular of the city was a huge opening. In 2011, CTJM formed to organize a campaign fueled by an expansive vision for justice informed by input from torture survivors and family members and extensive research on reparations. When the reparations package came to fruition in May 2015, it included a $5.5 million fund to provide financial compensation to survivors; curriculum about the Burge torture cases to be taught to eighth- and tenth-graders in Chicago Public Schools; a community center on the South Side providing specialized trauma counseling and other services for Burge torture survivors and their family members; free tuition at Chicago City Colleges for survivors and their family members, including grandchildren; the creation of a public memorial; and an official apology from the city.

While this legislation is limited in scope, providing reparations only to those who were violated by Burge’s torture ring, the legislation offers something else: a new paradigm for addressing the violence of policing. As Joey Mogul, the attorney-activist who drafted the Chicago Reparations Ordinance, said, “Chicago’s approach to systemic racial harm offers a glimmer of a possible future in which the nation as a whole might finally grapple with reparations for the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, and its direct descendant, mass incarceration, each of which echo through the Chicago Police Torture cases.”

In particular, for me, there are three enduring lessons from this recent struggle. First, reparations did not come readily from the courts or our elected officials. Despite numerous allegations of torture, for years the city and the courts not only turned a blind eye but also actively covered up the torture claims. While Burge and officers under his command were promoted, their victims faced convictions and long prison sentences, including death row for some. Victories in the long history of struggle in the Burge torture cases came about as a result of the consistent courage of the survivors and their family members, on-the-ground activism and organized pressure.

In the late 1980s community activists demanded an official investigation of the torture allegations and Burge’s removal from the police force. In the mid-1990s, Burge torture survivors on Illinois’ death row organized themselves from their prison cells; calling themselves the Death Row 10, they demanded new hearings in their cases and the abolition of the death penalty. In the 2000s, unable to find justice in our own courts, human rights attorneys and activists took the Burge torture cases to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations Committee Against Torture.

From Burge being fired in 1993 to the commutations of all Illinois death sentences and pardons for four members of the Death Row 10 by Gov. George Ryan in 2003 to Burge’s prosecution and conviction in 2010 for lying about the torture, justice was sought, demanded and insisted upon by the survivors and their family members, community activists and attorneys. The reparations legislation that was passed in May 2015 was the culmination of decades of struggle around the Burge torture cases. “We are committed here in Chicago to ‘making’ Black Lives Matter,’” Mariame Kaba, abolitionist organizer and a co-leader of the #RahmRepNow campaign, wrote in a blog post she composed the day after a powerful Valentine’s Day rally in Chicago. “The reparations Ordinance is one concrete way that some of us have chosen to fight to make them matter. Through this decades-long struggle, we are prefiguring the world that we want to inhabit.”

The second lesson is that justice remained elusive for the torture survivors even after Burge was convicted in 2010. While Burge’s conviction was remarkable because of the court’s prior unwillingness to prosecute the perpetrators of torture — which stood in stark contrast to the zealous prosecution of Burge’s victims — it ultimately failed to address the systemic harm that was done to the survivors. Moreover, Burge’s conviction left the racism endemic to the criminal legal system and apparent in all levels of the city’s governance intact. Many activists and survivors, including myself, had raised the slogan to “Jail Jon Burge” and worked to secure his prosecution for years. But in the aftermath of his conviction in 2010, what became increasingly clear was that seeking justice within the confines of the legal system had limited our vision for justice. As abolition activists in Critical Resistance and INCITE! steadfastly remind us, prisons — even for those whose crimes are as heinous as Burge’s — don’t offer lasting solutions to violence and injustice.

Left to deal with this glaring reality, the same year that Burge was sentenced, a group of activists, educators, artists and an attorney came together to form the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM). Our first call to action was to announce an open call for speculative memorials commemorating the Burge torture cases. In essence, through this open call we were asking the public, and ourselves, to re-imagine what justice could look like in the Burge torture cases. CTJM received over 70 submissions, all of which were displayed in an exhibit entitled “Opening the Black Box: The Charge Is Torture” at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Sullivan Galleries. The original draft of the Reparations Ordinance for Burge torture survivors was first introduced to the public on the walls of this exhibit, as was Carla Mayer’s re-imagined Chicago flag with a fifth black star added to the existing four red stars. Later, emblazoned on movement T-shirts worn by protestors, Mayer’s flag became the iconic image of the reparations campaign.

The ordinance itself reflected the experiences and material needs expressed by the survivors. “I still have nightmares,” Anthony Holmes said. “I see myself falling in a deep hole and no one helping me to get out.”

“We are individuals that have suffered,” torture survivor Mark Clements said as hundreds of protesters delivered nearly 40,000 signatures on a petition supporting the Reparations Ordinance to Mayor Emanuel’s office in December 2014. “Each and every day, I suffer. Where is my psychological treatment?”

“I’ll be doggoned if this wasn’t a war that we were involved in, too, here in the United States,” Darrell Cannon said at a torture survivors’ roundtable organized by CTJM in 2011. “And we deserve reparations.”

Seeking reparations — and insisting on the term even when various City Council legislators questioned its use as divisive or controversial — meant centering the survivors’ experiences as well as the racial nature of this violence. At a time when police accountability is sought by many through prosecutions, the Chicago reparations package offers a new model for accountability, one providing tangible redress that criminal prosecutions fail to deliver.

The third lesson is that survivors have been central actors in this fight from the beginning. Their self-determination and insistence that their lives matter in the face of sadistic, racialized brutality carried out against them by white police officers, a hostile criminal legal system, racist media, and a corrupt city leadership from the mayor on down — stand as testaments to the power of people who fight for themselves against seemingly impossible obstacles.

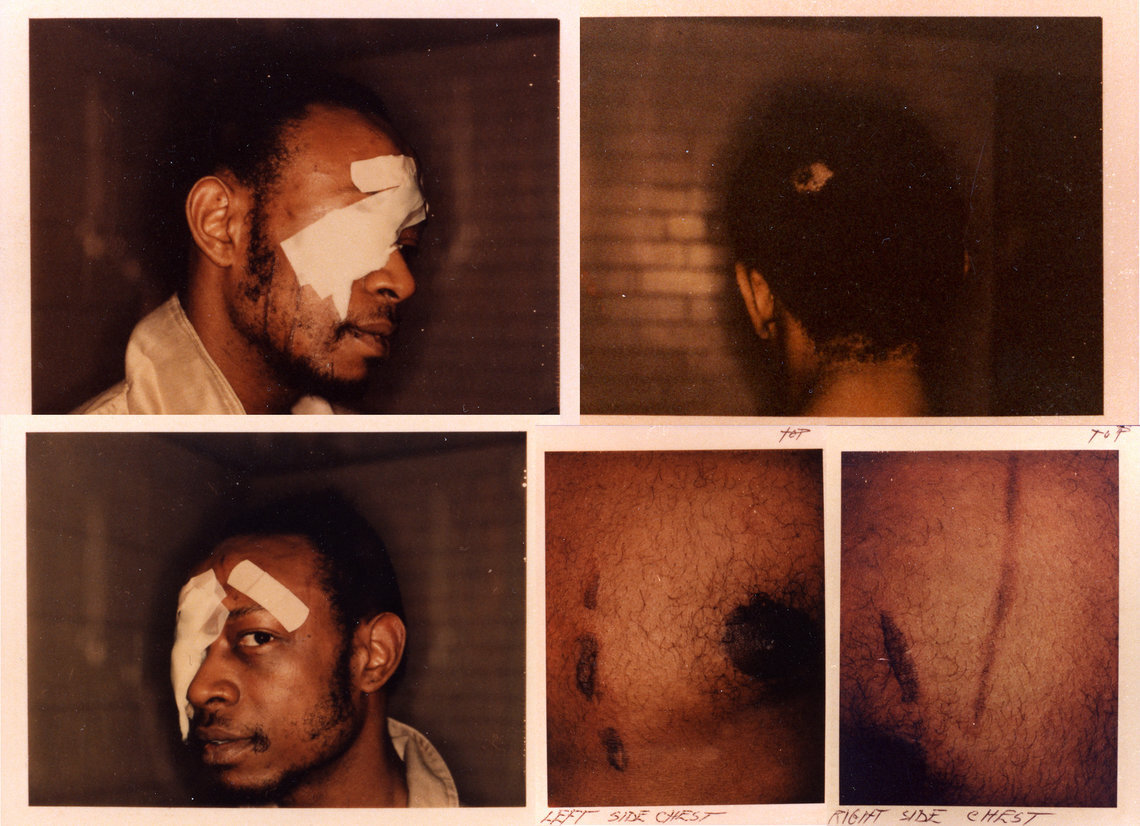

Andrew Wilson, convicted of killing two white police officers, dared to raise his voice and speak out about the torture he had endured. He’d been shocked with electrodes, burned by a radiator, suffocated with a plastic bag, kicked in the eye and badly beaten. Without a lawyer, he filed a civil suit in 1986, and his case would be pivotal in exposing the systematic torture carried out by Burge and his torture ring.

In his cell at Cook County Jail after he was tortured and arrested, Darrell Cannon used pen and paper as weapons in his defense. He drew in detail how three officers in Burge’s crew took him to an abandoned parking lot and proceeded to shock his genitals with an electric cattle prod and ram what they made him believe was a loaded shotgun into his mouth, pulling the trigger in a mock execution. His drawings were submitted as evidence, and Cannon says that even the psychiatrist for the state’s attorney said the level of detail in his drawings indicated that he had indeed been tortured. A vocal leader in the Chicago reparations campaign, Cannon tells his personal story time and time again in spite of how emotionally taxing it is for him. “It’s torturous any time I have to talk about this here,” Cannon said, “but it would be more torturous if I didn’t.”

Tortured, convicted and sentenced to death, Aaron Patterson refused to be silenced. Declaring that his cell was his “war room,” he formed the Aaron Patterson Defense Committee and fought fearlessly for his freedom. When he was pardoned by Gov. George Ryan in 2003, he jumped right into the activist scene vowing to fight against police violence and a corrupt legal system.

Calling themselves the Death Row 10, a group of African American men — all of whom were tortured by Burge and sentenced to death — organized collectively from their prison cells. Co-founder Stanley Howard announced the Death Row 10’s first rally in the fall of 1998, creating a flyer for the event by cutting and pasting words from newspaper and magazine articles. Though their demonstration was modest in size, with 60 to 70 family members and activists in attendance, it managed to get local and national media coverage. As The New Abolitionist reported, that night, prisoners and others nationwide saw mothers and family members of the Death Row 10 marching around the precinct carrying pictures of their sons. Interrupting the dehumanizing dominant narrative that cast death row prisoners as the worst of the worst, their campaign put a human face on the death penalty. For example, the Death Row 10’s efforts in conjunction with their mothers, who worked with lawyers and activists to organize a special meeting with then-Gov. Ryan, helped shift the tide of public opinion in a controversial campaign for commutations of all Illinois’ death sentences in 2003. In a historic act, Ryan pardoned four members of the Death Row 10 and granted blanket commutations of the state’s 167 death sentences, a move that would lead to the abolition of the state’s death penalty eight years later. From the abolition of the death penalty in Illinois to reparations legislation in Chicago, Burge torture survivors have been at the center of these struggles.

The last chapter in this story has yet to be written. There is much more to do in order to create a society based on respect for human rights and dignity; there is much to accomplish in terms of demilitarizing cities, ending police violence and building the power of communities to control the resources that keep them safe; there is more to organize in terms of linking racial justice with economic and global justice. But to this point, the story teaches us a lesson we must never forget: The power of a people organized and mobilized in the cause of justice can break walls and make history.

— Alice Kim is an educator, cultural organizer and justice activist based in Chicago. She is a co-founder of Chicago Torture Justice Memorials and was an organizer with the Campaign to End the Death Penalty, where she worked closely with the Death Row 10 and their family members to bring attention to their cases. She was instrumental in the campaign for blanket commutations of Illinois death sentences by former Gov. George Ryan in 2003. She is co-director of the Prison+Neighborhood Arts Project’s cultural organizing and community building initiative and facilitates a think tank at Stateville Prison. She serves on the steering committee of the Illinois Coalition for Higher Education in Prison’s Freedom to Learn Campaign and is a Woods Fund board member. She is co-editor of “The Long Term: Resisting Life Sentences, Working Toward Freedom” and is currently working on a book about the struggles for justice in the Jon Burge torture cases with Joey Mogul. Kim is director of human rights practice at the University of Chicago’s Pozen Family Center for Human Rights.

Excerpted from the essay “Breaking Walls: Lessons from Chicago” in “The Long Term: Resisting Life Sentences Working Toward Freedom,” edited by Alice Kim, Erica Meiners, Jill Petty, Audrey Petty, and Beth E. Richie. Haymarket Press, 2018.

> Termination of Jon Burge from the Chicago Police Department

Excerpted from “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” by Joey L. Mogul. Public Interest Law Reporter Symposium, 2015.

The People’s Law Office, following the leads of an anonymous police source called “Deep Badge,” tracked down 25 Black men in addition to Andrew Wilson who alleged they were tortured at Area 2 Police Headquarters, confirming that Wilson’s torture was not an isolated incident, but simply one instance in a larger racist pattern and practice of torture. This was powerful evidence to corroborate Wilson’s allegations and that have been admitted pursuant to FED. R. EVID. 404(b) at his civil rights trial. The judge presiding over Wilson’s civil proceedings in 1989, however, would not admit this relevant and damning evidence. Instead, the judge allowed Burge’s defense counsel to present a slew of irrelevant evidence relating to the murders of Officers William Fahey and Richard O’Brien. Consequently, Wilson did not prevail in the trial court.

Fortunately, the struggle for justice was not confined to the courtroom alone. Citizens Alert, a police accountability organization, along with the Task Force to Confront Police Violence, armed with the evidence from Wilson’s civil case and exposés by journalist John Conroy on Burge’s reign of torture, demanded that Burge and other implicated detectives be fired from the CPD. Their campaign was endorsed by 50 local organizations, ranging from Clergy and Laity Concerned to Queer Nation, who joined them in demonstrations at the federal courthouse, Police Headquarters, and Chicago’s City Hall. They were relentless in their efforts to hold Burge and others accountable.

Eventually, the political winds began to change. The Office of Professional Standards (OPS), the department responsible for investigating allegations of excessive force by members of the CPD, re-opened its investigation and sustained Wilson’s allegations of torture. In 1990, OPS also conducted a larger investigation into allegations of torture and abuse from Area 2 and concluded, in what is now referred to as the Goldston Report, that the abuse at Area 2 Police Headquarters was “systematic,” and that “(p)articular command members were aware of the systematic abuse and either actively participated in it or failed to take any action to bring it to an end.”

The CPD initiated disciplinary hearings and subsequently terminated Burge from the department in 1993, representing a significant victory for accountability that could not have been achieved through civil litigation alone.

> The Death Row 10 and the Campaign to End the Death Penalty

Excerpted from “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” by Joey L. Mogul. Public Interest Law Reporter Symposium, 2015.

At the time of Burge’s termination from the CPD in 1993, there were 10 known Burge torture survivors on Illinois’ death row. These men were seeking relief from criminal convictions and death sentences in appeals and post-conviction petitions, arguing that there was a pattern and practice of torture within the CPD, citing Burge’s termination and the findings made in the Goldston Report as strong corroboration of their allegations that their confessions were physically coerced. Yet, they were routinely denied relief by the Circuit Courts and Illinois Supreme Court, despite this new, game-changing evidence.

The men on the row were fed up with waiting for justice in the courts, and seeking to control their own lives and destinies, they courageously began to organize themselves by calling themselves “The Death Row 10.” The Death Row 10 urged their family members to attend court hearings and speak out on their behalf. They also wrote to organizers and activists beseeching them to stage teach-ins and protests about their cases and plight for justice. Aaron Patterson, one of the most prominent survivors on death row, boldly called and wrote to members of the press from his prison cell demanding the press report on his case and court proceedings and question Burge and the other officers responsible for the torture.

Family members responded to their calls, becoming their ambassadors, fearlessly and tirelessly speaking out in support of their loved ones, attending rallies, going to churches and speaking to scores of students about the Death Row 10. The Death Row 10 joined forces with the Campaign to End the Death Penalty (CEDP) to organize events, featuring members of the Death Row 10 calling in to speak to audiences “live from death row” in a style first popularized by political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal. In so doing, the survivors made it clear that they would speak for themselves, ignoring the admonition of counsel that anything they said could be used against them in their court proceedings. According to Alice Kim, an organizer with the CEDP who later helped to co-found the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, by providing a platform for the voices of the Death Row 10 to be heard directly by audiences all around the country, survivors and organizers were able to interrupt the prevailing narrative of death row prisoners as the “worst of the worst.”

As the campaigns for the Death Row 10 and Patterson were gaining traction, the press was questioning the fairness and efficacy of the death penalty. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, 13 people sentenced to die were exonerated on the basis of innocence, leading then-Illinois Gov. George Ryan to issue a moratorium on all executions on January 31, 2000, becoming the first state in the nation.

As it was becoming increasingly clear that Gov. Ryan would not seek reelection in 2002, several lawyers representing capital defendants hatched a plan to seek clemency on behalf of all those on Illinois’ death row. The effort for clemency eventually became a highly visible public campaign, leading to over 200 public clemency hearings before the Illinois Prisoner Review Board where both family members of people on death row, including the Death Row 10, and family members of murder victims spoke on behalf of their loved ones. The hearings were emotionally charged and heartbreaking, as attention was focused on the flawed nature of the criminal legal system, including the role played by the Burge torture cases, while also exposing the wells of pain and loss among families of those no longer in the world. Ultimately, the campaign was successful.

On January 2, 2003, Gov. Ryan pardoned four of the Burge torture survivors — Madison Hobley, Stanley Howard, Leroy Orange and Aaron Patterson — on the basis of innocence. The following day, Gov. Ryan declared the death penalty was fatally flawed and commuted the death sentences of all prisoners then on death row.

It was another phenomenal victory for justice that did not come through the courts, but rather, was the product of extrajudicial actions by survivors, attorneys and activists in concert that later contributed to the abolition of the death penalty in Illinois in 2011.

> The Conviction of Jon Burge: the Campaign to Prosecute Police Torture and the UN Committee Against Torture

Excerpted from “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” by Joey L. Mogul. Public Interest Law Reporter Symposium, 2015.

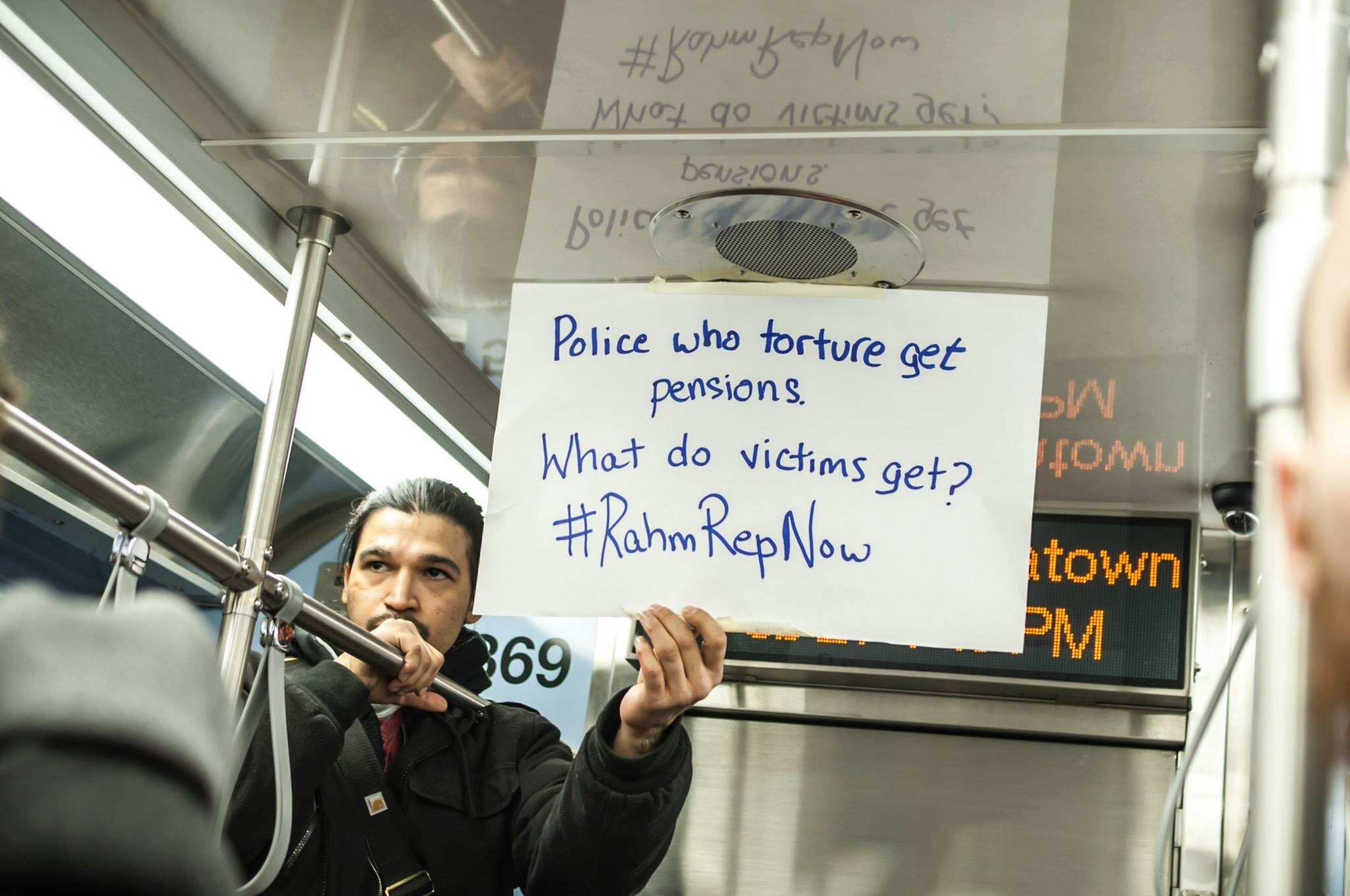

As efforts to support the Death Row 10 were gaining momentum, it also became painfully clear that Burge and other officers guilty of torture enjoyed impunity for their crimes. While Burge was fired by the CPD, he retained his city-funded pension, and no other officer was terminated, let alone disciplined. Instead, many were promoted and allowed to retire with their full pensions intact.

In response to this injustice, I, as part of a group of death penalty attorneys who represented some of the Death Row 10, along with several organizers, started the Campaign to Prosecute Police Torture (CPPT). The goal of the campaign was to secure the appointment of a special prosecutor to investigate and prosecute Burge and others. CPPT was well aware that the statute of limitations had expired for prosecuting any crimes of torture that the officers had committed but believed that the officers could and should be held responsible for their crimes of perjury and obstruction of justice for consistently denying that they engaged in acts of torture in ongoing court proceedings.

While the legal effort prevailed and Presiding Judge of the Cook County Circuit Court Criminal Division Paul Biebel Jr. granted the petition to appoint a special prosecutor, the campaign did not control who would be chosen as a Special Prosecutor. Two former Cook County Assistant State’s Attorneys who worked under Richard J. Daley at the State’s Attorney’s Office, Edward Egan and Robert Boyle, were selected to lead the investigation into Burge and other detectives’ alleged crimes. After two years, it became apparent that their investigation was not going to lead to any indictments whatsoever.

Then, in 2004, the pictures of the torture, abuse and harassment of Iraqi detainees by U.S. military officers at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were published, causing a national and international uproar about the use of torture practices by military officials. In a stark contrast, the torture of Black people by law enforcement officials in the U.S., including the torture on Chicago’s own South Side, continued to go without redress. The sharp juxtaposition propelled Standish Kwame Willis, a renowned civil rights attorney and activist who later founded Black People Against Police Torture (BPAPT), to mount an effort to bring the Burge torture cases to international fora.

In May of 2006, the United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT) was evaluating the U.S. government’s compliance with the U.N. Convention Against Torture in Geneva, Switzerland. While the U.S. delegation implicitly acknowledged there were some “missteps” during the “War on Terror” sparked by the September 11, 2001, attacks, they insisted the U.S.’s record in complying with the Convention on U.S. soil was commendable. Domestic advocates also attended the hearings and had the opportunity to present evidence of torture committed in the U.S. by police, prison and immigration officials. As part of this effort, I had the privilege of presenting the Burge torture cases to the Committee members.

After two days of formal hearings with the U.S. governmental delegation and reviewing reams of reports and primary sources, the U.N. CAT issued a scathing indictment of the U.S. government’s failure to comply with the U.N. Convention Against Torture on May 19, 2006. In addition to calling on the U.S. government to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay and prosecute the chain of command at Abu Ghraib for crimes of torture, the Committee noted the “limited investigation and lack of prosecution” at Area 2 and 3 Police Headquarters, and it called on the U.S. government “to bring (the) perpetrators to justice.”

It was a momentous occasion, validating the long silenced, disbelieved, and ignored voices of the torture survivors, many of whom were deeply moved by the notion of the highest human rights body in the world publicly holding the U.S. accountable on the world stage for the torture they endured. It was also poignant for the Committee to equally condemn the torture practiced here at home as well as that done abroad. The U.N. CAT’s findings made national and international news, airing on all of the local nightly news channels. Once again, the whole world was watching Chicago.

A month after the U.N. CAT issued its findings, the special prosecutors concluded their investigation, finding that Burge and other detectives under his command committed crimes of aggravated battery and armed violence, surprising no one. However, the special prosecutors claimed they could not prosecute Burge and others because the statute of limitations had expired — -not only on these physical violations, but also on the crimes of perjury or obstruction of justice for repeated false testimony denying the acts of torture. To briefly summarize the results of their four-year, $7 million investigation, it was too bad, so sad, time to close the book on this unfortunate story.

Torture survivors, their family members, CPPT and other activists and attorneys refused to take no for an answer. Organizations, including BPAPT, marched in the streets and held rallies at Daley Plaza. We convened a hearing at the Cook County Board and obtained the passage of a resolution calling on the U.S. Attorney’s Office to prosecute Burge and his men for the crimes they committed. Others organized a letter writing campaign and petition drive demanding that the U.S. Attorney in the Northern District of Illinois bring charges against Burge.

A year and half after the U.N. CAT issued its findings, Burge was indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the Northern District of Illinois and U.S. Department of Justice for two counts of perjury and one count of obstruction of justice for falsely denying he and others engaged in torture in a civil rights case.

On June 28, 2010, after torture survivors Anthony Holmes, Melvin Jones, Shadeed Mu’min and Gregory Banks courageously testified against Burge, Burge was found guilty of all three counts, and in January 2011 he was sentenced to serve four and half years in prison.

> The Fight for Reparations: #RahmRepNow, We Charge Genocide, and the passage of Reparations Legislation

Excerpted from “The Struggle for Reparations in the Burge Torture Cases: The Grassroots Struggle That Could,” by Joey L. Mogul. Public Interest Law Reporter Symposium, 2015.

While Burge’s conviction was significant, the victory was a hollow one. Burge’s conviction failed to address the material needs of the torture survivors. Many of the survivors continued to suffer psychologically from the torture they endured, experiencing flashbacks and nightmares of their interrogations, but there was no place for them to obtain any psychological counseling or assistance. Moreover, the vast majority of torture survivors, including Holmes, Jones and Mu’min, had no legal recourse to seek any financial compensation or redress. The statute of limitations on any civil claims they could have brought expired decades ago, as many languished in their prison cells fighting their criminal prosecution and convictions. As BPAPT argued in 2008, the Burge torture survivors were entitled to reparations.

In January 2011, on the heels of Burge’s conviction, Chicago Torture Justice Memorials (CTJM), a group of artists, activists, educators, survivors and attorneys, formed to focus on the creation of public memorials, one component of reparations, in the Burge torture cases.

In October of 2012, CTJM mounted its first exhibition, titled “Opening the Black Box: The Charge Is Torture” featuring over 70 speculative memorials submitted. They included a wide range of artistic mediums, including architectural proposals, photographs, soundtracks and sculptures. Lucky Pierre, an art collective, created 100 direct actions the public could take in response to the torture cases. Teachers and professors submitted their syllabi on how they would teach the Burge torture cases, from high school art classes to college seminars on international human rights. Carla Mayer, a CTJM member, submitted a proposal to add an additional star to the Chicago flag to memorialize the Burge torture cases, which later became the iconic image in the reparations campaign. I submitted a draft of the reparations ordinance as a speculative memorial.

As we continued to reflect on reparations in the Burge torture cases, CTJM focused on international human rights law and the principles of restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition. We also researched reparations schemes for other gross human rights violations in other countries, looking at redress provided to the survivors of the “Dirty War” in Argentina, those tortured and killed under General Augosto Pinochet’s regime in Chile, the torture of the Mau Mau by British colonizers in Kenya, and those tortured in South Africa. We looked to the redress provided to Black survivors of a massacre by a white mob in the Rosewood, Florida in 1923; the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, providing compensation to the Japanese Americans and Aleut residents who were forcefully detained and/or relocated during World War II; and the compensation provided to people forcibly sterilized in North Carolina in the 1900s. Relying on these examples as templates and reflecting an input from the survivors and submissions to the art exhibition, I revamped the ordinance, striving to root it in a restorative justice framework.

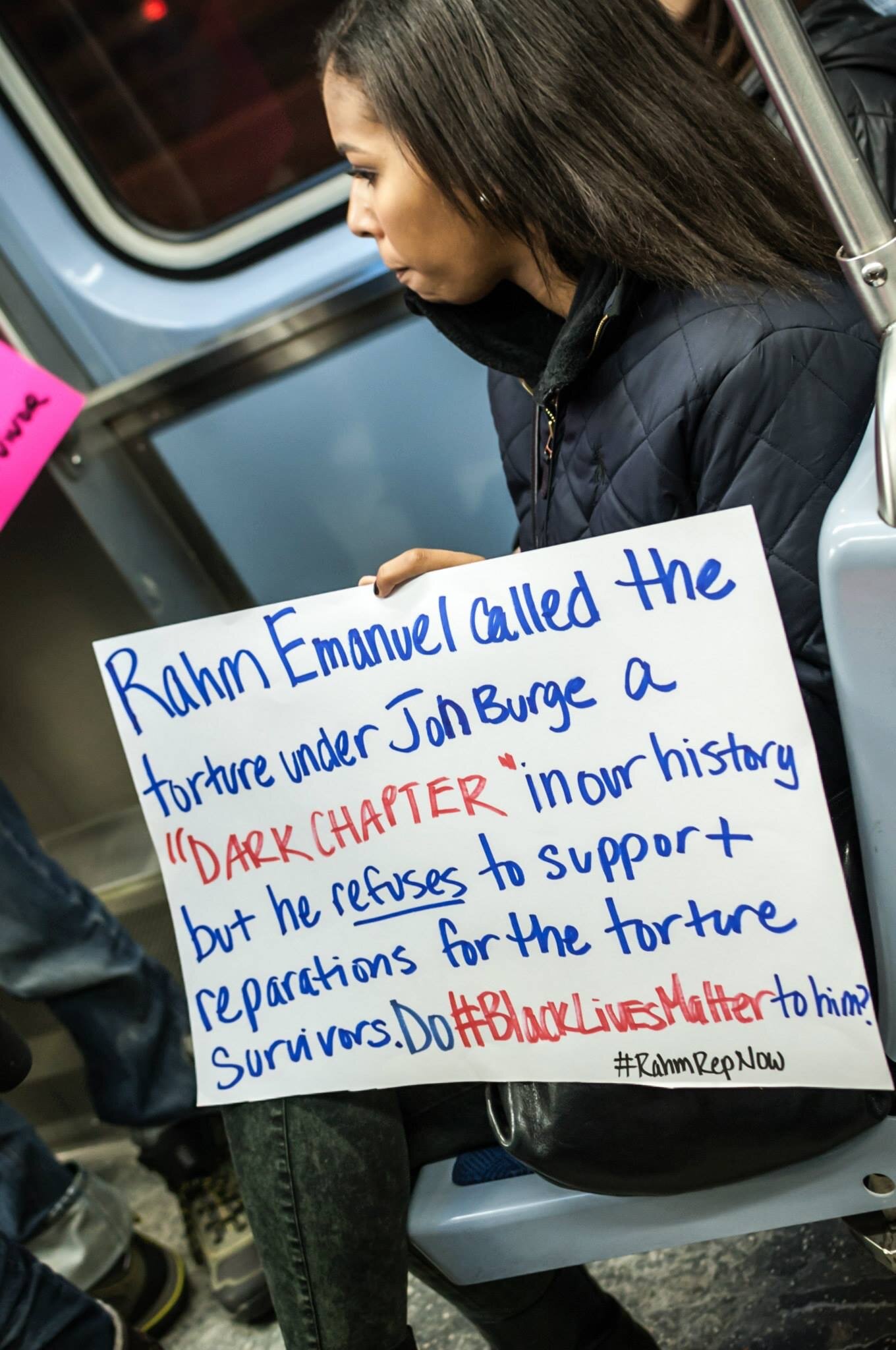

On September 11, 2013, the Council voted to approve a $12.3 million settlement for Ronald Kitchen and Marvin Reeves, both of whom were tortured and wrongfully convicted and spent 21 years in prison for a quintuple murder they did not commit. Shortly after the vote, Fran Spielman of the Chicago Sun-Times asked Mayor Rahm Emanuel whether the settlement served as an apology for the torture cases. Mayor Emanuel acknowledged that the cases were a “dark” chapter and a “stain on the City’s reputation” but said that he wanted to build a city for the future. He summarized his sentiments by saying, “I am sorry this happened. Let us all now move on.”

Mayor Emanuel’s “apology” infuriated many of the torture survivors and other members of CTJM who felt it was half-hearted, insincere and dismissive. It motivated us to file the reparations ordinance before the City Council and begin the reparations campaign (#RahmRepNow) to let Mayor Emanuel and the city know that we could not and would not move on, and that we would continue to demand that the city of Chicago take responsibility and make amends for the enormous, ongoing harm caused in the Burge torture cases.

When we filed the ordinance, many of us never thought in our wildest dreams it would pass. Although we had little experience with City Council politics, we educated ourselves on how to reach out to and gain aldermanic support for the ordinance. While there were many setbacks along the way, over time, our call for justice for the survivors of police torture gained powerful allies, including Amnesty International USA, which joined the campaign in the spring of 2014. By September 2014, we were able to secure the public endorsement of 26 aldermen and women, only one vote shy to make the bill into law. We were committed to making the reparations ordinance an issue in the upcoming local elections.

As election season was underway, the U.N. Committee Against Torture was again reviewing the U.S. government’s compliance with the U.N. Convention Against Torture in November of 2014. Earlier that spring, a new intergenerational grassroots group called We Charge Genocide (WCG) formed after one of their dear friends, Dominique “Damo” Franklin, a young Black man, died after he was tased by Chicago Police officers. Damo’s friends were devastated. Mariame Kaba, a revolutionary thinker, abolitionist and founder of Project NIA, developed the ingenious idea of sending an all-youth of color delegation to the U.N. to once again raise the issue of racist police violence — this time centering the experiences of youth of color in Chicago, and naming the delegation in honor of the historic Civil Rights Congress’s petition “We Charge Genocide” filed with the United Nations General Assembly in 1951. The delegation, along with a CTJM representative, attorney Shubra Ohri, also asked the U.N. CAT to support the reparations ordinance.

The WCG delegation staged a protest inside the U.N. hearing room in Geneva, Switzerland, capturing the attention of the U.N. Committee members, the U.S. delegation and the international media. Weeks later, on November 20, 2014, the U.N. Committee issued its report citing its ongoing concerns regarding racist police violence in Chicago, noting particular concerns about violence against African American and Latinx youth, and again cited the Burge torture cases, calling on the U.S. Government to support the passage of the “Chicago Police Torture Reparations Ordinance.” Soon thereafter, CTJM and Amnesty International joined forces with Project NIA and WCG to form the Reparations Coalition.

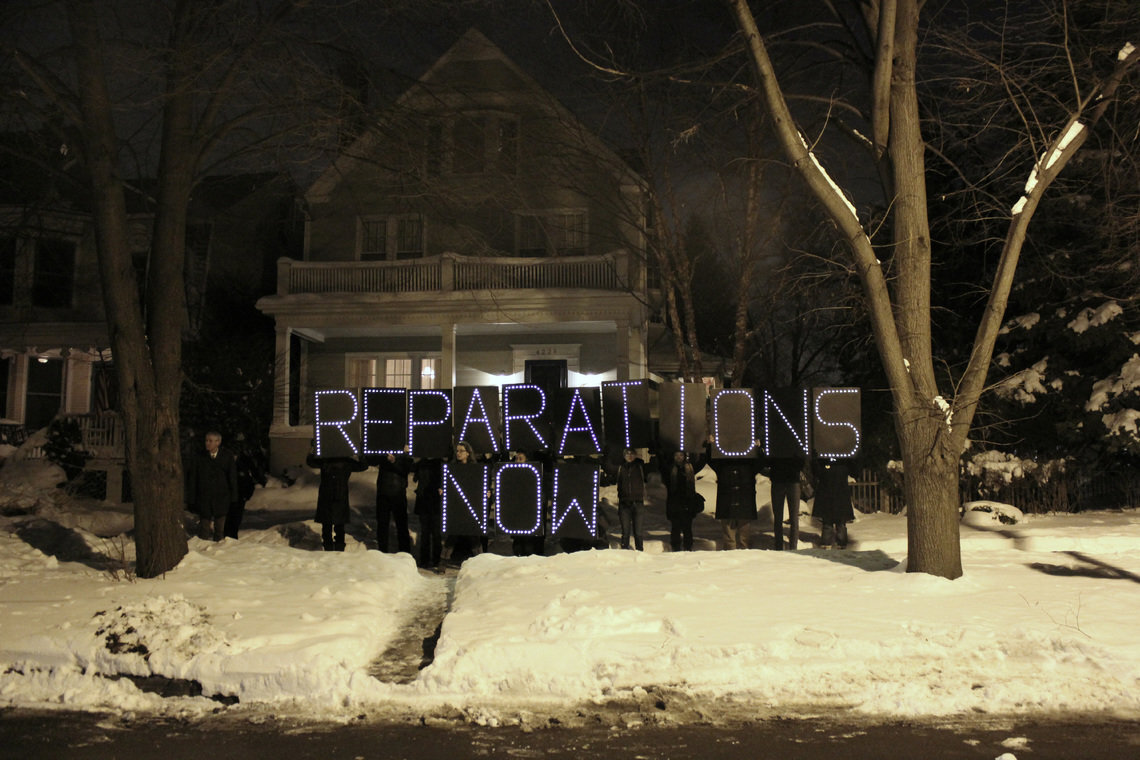

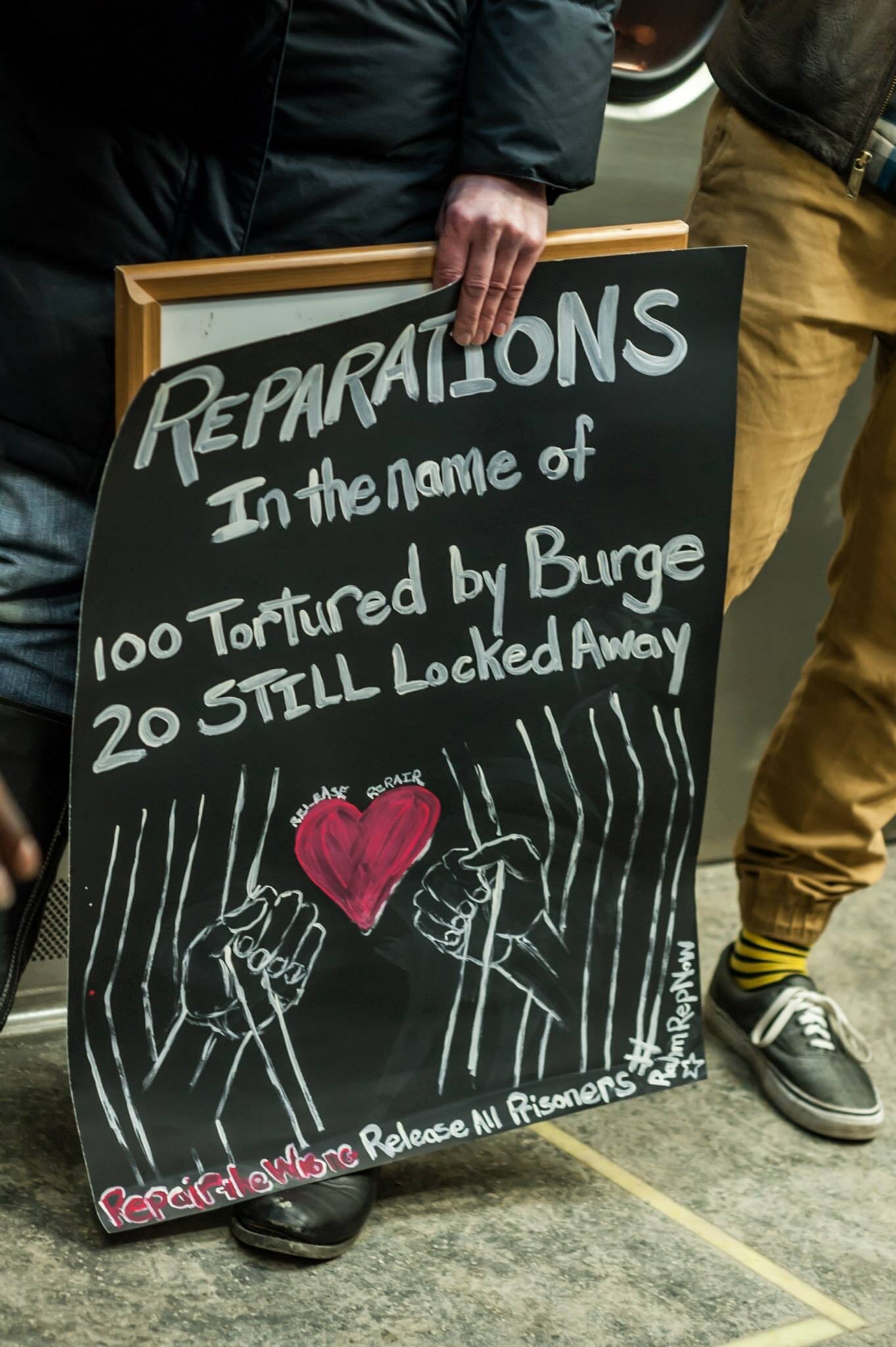

Over the next six months, during the height of the election season, the Reparations Coalition, along with several allies, held events and direct actions throughout the city demanding that Mayor Emanuel, other mayoral candidates and individuals seeking aldermanic office support the ordinance. People sang in, died-in and curated a pop-up art memorial at City Hall; held a Kwanzaa action at Daley Plaza; created a light installation demanding “Reparations Now” outside of Mayor Emanuel’s home; took over CTA trains; and held Twitter power hours, using social media every step of the way with the unifying hashtag #RahmRepNow. Fueled by the attention brought to police violence against Black people by the Black Lives Matter movement, the reparations ordinance became the key demand at every police brutality demonstration in the city.

On Valentine’s Day 2015, on the eve of the mayoral election, we held a raucous rally for reparations at the storied Chicago Temple with hundreds in attendance. We called on Mayor Emanuel to “have a heart” and pass the reparations ordinance, and we passed out a voter’s guide entitled “Who’s Right on Reparations” listing which of the mayoral and aldermanic candidates supported the ordinance. Days after the rally, CTJM received a call from Corporation Counsel Steve Patton asking for a meeting to discuss the ordinance.

The following week, Mayor Emanuel failed to get fifty percent of the vote, prompting a runoff election in April of 2015. We then had a series of meetings with Mayor Emanuel’s administration that were at times heated and contentious. We succeeded in forcing the administration to meet many of our demands, but we also made some very painful compromises. Right after the runoff election, we reached an agreement with Mayor Emanuel and his administration.

Ultimately, the legislation that passed as a result of the negotiations provided for the creation of a $5.5 million reparations fund to pay up to $100,000 to each eligible Burge torture survivor still alive; the provision of counseling services to police torture survivors and family members at a dedicated facility on the South Side of Chicago; free tuition at Chicago’s City Colleges for Burge torture survivors and their family members, including their grandchildren; job placement for Burge torture survivors in programs for formerly incarcerated people; priority access to city of Chicago’s reentry support services, including job training and placement, counseling, food and transportation assistance, senior care, health care, and small business support services; a formal apology from the mayor and City Council for the torture committed by Burge and his men; a permanent public memorial acknowledging the torture committed by Burge and his men; and a history curriculum on the Burge torture cases to be taught to all Chicago Public School students in the eighth and tenth grades.

On May 6, the reparations legislation was presented to the City Council for a vote. Fourteen of the torture survivors were in attendance, and upon the unanimous passage of legislation, they received a standing ovation from Mayor Emanuel and the council members. At the victory party that night, Darrell Cannon, a leader of the reparations campaign, marveled with tears in his eyes: “Reparations? For Black people? In America?”

The passage of the reparations legislation made history. It is the first time a municipality in the U.S. has provided reparations for racially motivated police violence. The movement made the city of Chicago provide money to survivors and for services it was not legally obligated to.

The reparations package is not a perfect solution, and it is not a panacea for stopping and redressing racist police violence. But for decades, we have witnessed this perpetual cycle of racist police violence, righteous responses and then failed prosecutions of killer and torturing police officers. A call for reparations that is expansive in scope and that centers the needs of people targeted for police violence may be a new way for us to think about accountability and justice for police brutality in the face of our fatally flawed legal system.